Markets and strategies

Fed: when "data dependency" is troubled by "data"

In recent quarters, central banks have regularly focused on "data dependency" but the latter increasingly often is troubled by... "data".

Published on 18 October 2024

The example of the Fed in recent weeks is particularly striking from this point of view. As a reminder, from the Jackson Hole central bankers' conference, Jerome Powell formalized the decentering of the price stability objective and the refocusing on the full employment objective: in other words, with inflation having generally normalized, the Fed is now addressing the risk of a deterioration in the labor market.

However, while several indicators (the “employment” component of the ISM and PMI, hiring rates, quit rates, Beige Book, etc.) indicated a continued slowdown in the US labor market, the September job report, published on October 4, sent a completely opposite signal with strong job creations (254,000) and a drop in the unemployment rate to 4.1%.

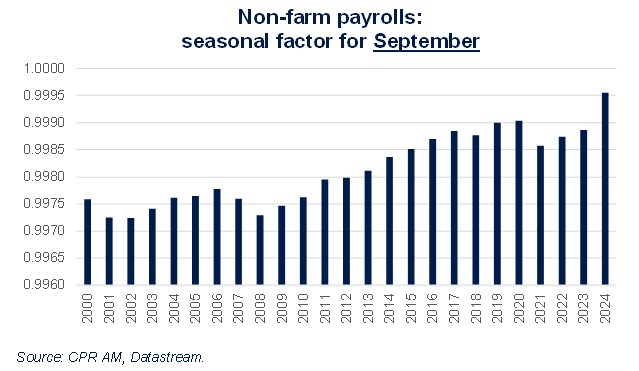

Even more than usual, this job report should be analyzed with caution, largely because of a sudden change in seasonal adjustment: indeed, if the same seasonal adjustment had been taken for September 2024 as for September 2023, job creations would have been 145,000, roughly in line with the consensus (140,000) ... and the market consequences would have been very different. Indeed, the fact that this job report is contrary to other statistics has led to a notable revision of monetary policy expectations and therefore a sharp rise in long-term rates.

At the same time, the minutes of the Fed’s most recent policy committee meeting show that FOMC members judged that “the evaluation of labor market developments had been challenging, with increased immigration, revisions to reported payroll data, and possible changes in the underlying growth rate of productivity.”

Board member Christopher Waller also noted that “volatile data have made this is a weird time for policymakers.”

This touches on one of the problems with the “data dependency” approach: what should central banks conclude when different statistics on the same topic send conflicting signals? Or when these different statistics are tainted by potentially very disruptive but difficult to detect statistical biases?

On these issues, James Bullard wrote while he was still president of the St. Louis Fed: “Data dependency is sometimes misinterpreted as meaning decisions are based on the data released just before an FOMC meeting. That interpretation is far too narrow and inconsistent with good monetary policymaking. Rather, the decisions should be based not only on the current dynamics in the data but also on longer-run trends and expectations for data going forward.”

And that’s probably what FOMC members will do: follow trends in a wide range of labor market data, not just the latest jobs report. That’s what will lead the Fed to cut rates decisively in the months ahead.