The big challenges of COP 28

Published on 8 December 2023

2023: a record year, according to the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO)

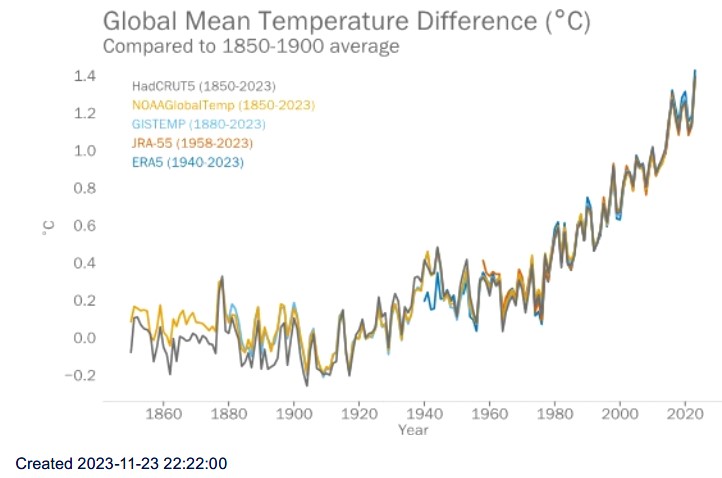

In 2023 (up till October), the average global surface temperature exceeded its 1850-1900 average by about 1.40 °C (±0.12°C). The months of June, July, August, September and October were all the warmest on record. It is almost certain that 2023 will be the warmest year in the 174 years of recorded observations, exceeding the two previous warmest years, 2016 and 2020. The WMO expects El Niño to make the heat even worse in 2024.

Between April and September, average temperatures at the surface of the ocean reached a record level for this time of the year.

An initial assessment of action taken globally to counter climate change since 2015

With the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015, signatory countries agreed that they had not done enough until then to meet the target of capping warming at 1.5°C compared to the pre-industrial era. Governments were therefore called upon to strengthen their climate action plans every five years, while updating their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and adopting a long-term strategy out to 2050. NDCs were first updated in 2020, and a new update is planned by 2025 with objectives set for 2035.

In September 2023, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) released its first assessment, called the Global Stocktake, since COP 21 in 2015. It was based on contributions from the 137 countries that had disclosed the actions they had taken to hit the Paris Agreement targets. The Global Stocktake reported on progress that had been made in combatting climate change, shortcomings, and priority actions to be taken to remediate those shortcomings. This was an important contribution in the run-up to COP 28 and it is expected to lead to new government commitments at the end of the meeting.

A “wide gap in mitigation policies”

Unsurprisingly, the Global Stocktake reported that global progress had not been enough to keep climate change below 1.5°C. While many countries have pledged to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, their 2030 targets are far from being enough to do so.

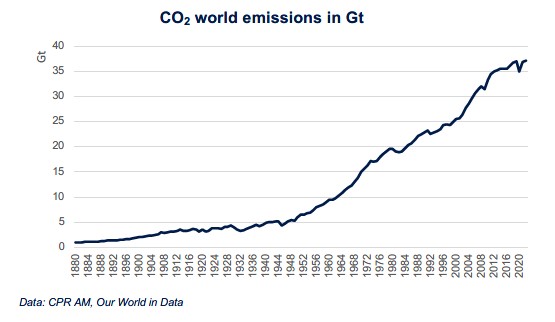

- Emissions have still not peaked globally

Global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have peaked in developed economies and in some developing ones, but not yet on a global basis. The Global Stocktake is based on scientific data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and reports that GHG emissions must peak by no later than 2025 and recede by 43% by 2030 and by 60% by 2035 (compared to their 2019 level) in order to cap climate change at 1.5°C, with a probability of 66%.

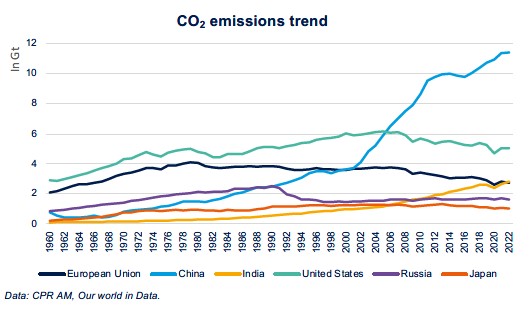

- Countries’ commitments in the NDCs are quite far off target

Current NDCs are on a trajectory pointing towards 2.9°C barring conditional measures, and towards 2.5°C assuming conditional measures are taken. The gap vs. emissions that would cap warming at 1.5°C in 2030 ranges between 20.3 and 23.9 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent, compared with global emissions of 57.4 gigatonnes CO2 equivalent in 2022.

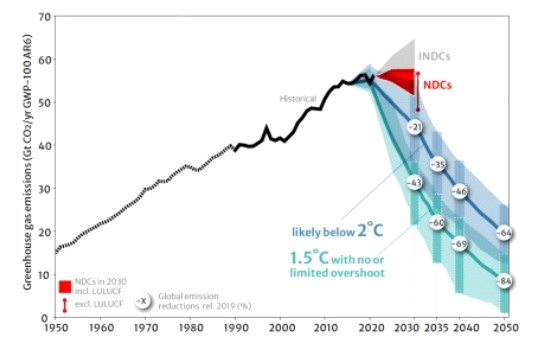

Historical emissions from 1950, projected emissions in 2030 based on nationally determined contributions, emission reductions required by the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

To manage to rapidly reduce emissions of CO2 and other GHGs, the report suggests that economies will have to betransformed in “all sectors” and in all contexts. The priority nonetheless remains the energy sector, which is the main source of GHGs worldwide. Action must be taken on both the supply side, by developing renewable energies and phasing out all fossil fuels, and on the demand side, through electrification and energy efficiency. The International Energy Agency has released quantified objectives on each of these points that would bring the CO2 emission reduction goals within reach.

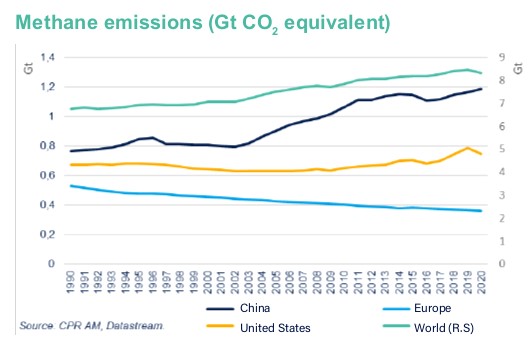

Another major challenge for the energy sector is combatting methane1 emissions from oil & gas fields. In 2021, this led to the creation of the Global Methane Pledge, launched by the US Europe, and which brings together those countries that have pledged to reduce their methane emissions by 30% by 2030.

Halting and reversing deforestation by 2030, and restoring and protecting natural ecosystems are also expected to increase large-scale absorption of CO2. Agriculture, deforestation and, more generally, changes in soil use are responsible for 22% of GHG emissions.

COP 28 and financing climate action

Another important issue for COP 28 is expanding developing countries’ access to financing of climate initiatives.

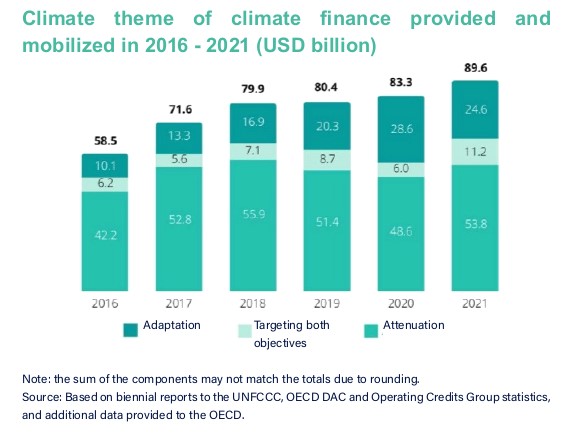

- In 2009, developed countries pledged to increase financing in the form of loans and subsidies to $100bn annually to help developing countries in their climate initiatives. Financing has ramped up very gradually and most of it still consists of loans. According to an OECD estimate2, developed countries raised $89.6bn in financing in 2021.

- In 2022, COP 27 approved the principle of creating a “Loss and Damage” fund for the 46 developing countries that are especially vulnerable to climate change, but without laying out the contours. The fund became operational at the start of COP 28 in obtaining almost 400 million dollars in contributions. These pledges were just a start, as the issue amounts to billions of dollars.

- The issue of splitting financing between climate change mitigation and adaptation has also been raised. While mitigation remains the core goal, climate policies must allocate an increasing share to policies for adapting to climate change, particularly in the most vulnerable countries. The share of adaptation in financing climate action rose from 20% in 2017-2018 to 28% in 2019-2020, but that is still not enough.

The UN estimates that adaptation in developing countries will require growing financing needs, amounting to $300bn per year by 2030, then $500bn per year by 2050.

Beyond the fact that financial commitments currently fall short of the sums needed to address these challenges, the World Bank calls for “designing strategies for climate change adaptation” and for a comprehensive approach, rather than less effective sector-based and fragmented measures.

Based on the first global assessment of climate action, much progress still has to be made in the coming years to meet Paris Agreement goals. This will require in-depth changes in all economic sectors, starting with energy. Commitments to combat methane emissions, exit coal, and, more generally, fossil fuels will be key to judging the success of this latest COP. Raising financing commitments is also essential for implementing the decisions that have been made.

1. Methane’s warming impact is 86 times greater than CO2 on a 20-year horizon.

2. Climate financing provided and mobilised by developed countries in 2013-2021, OECD, November 2023