India, a new golden age

Amrit Kaal – “the golden age” in Sanskrit – looks like an apt description for the phase the Indian economy is going through right now. For India appears to be immune to the global slowdown, and its momentum is drawing the attention of international investors – and rightly so – triggering a bull market in local equities.

Published on 7 March 2024

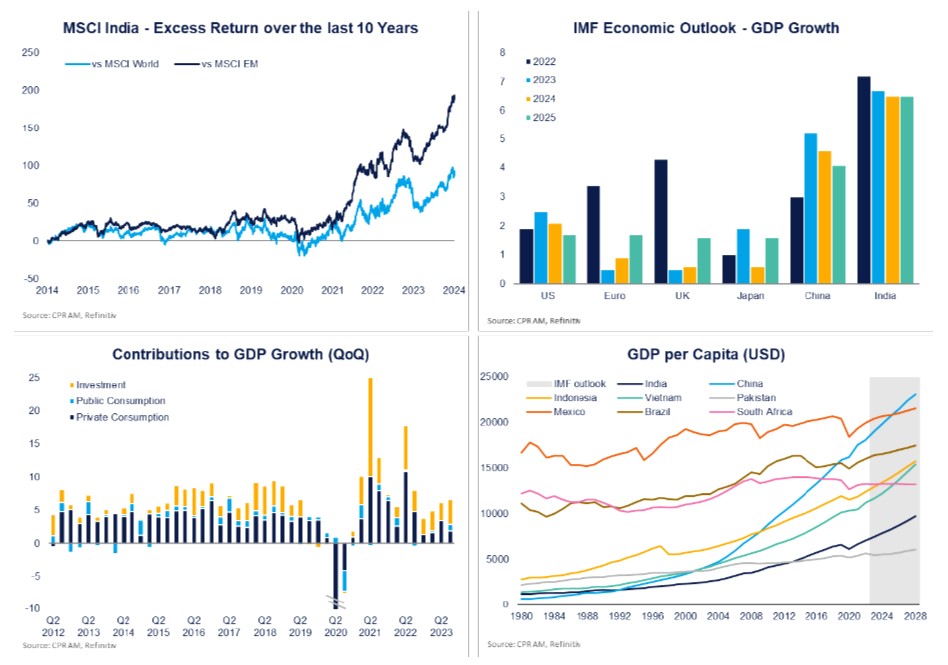

From May 2020 to January 2024, the MSCI India achieved an annualised return of 26.7%, double that of the MSCI World and almost five times that of the MSCI EM. On top of economic figures, the buzz over India was further stoked in 2023 by several head-grabbing events – India hosted the G20 summit; it became the world’s most populous country and its fourth-largest equity market; and it even landed a probe on the Moon.

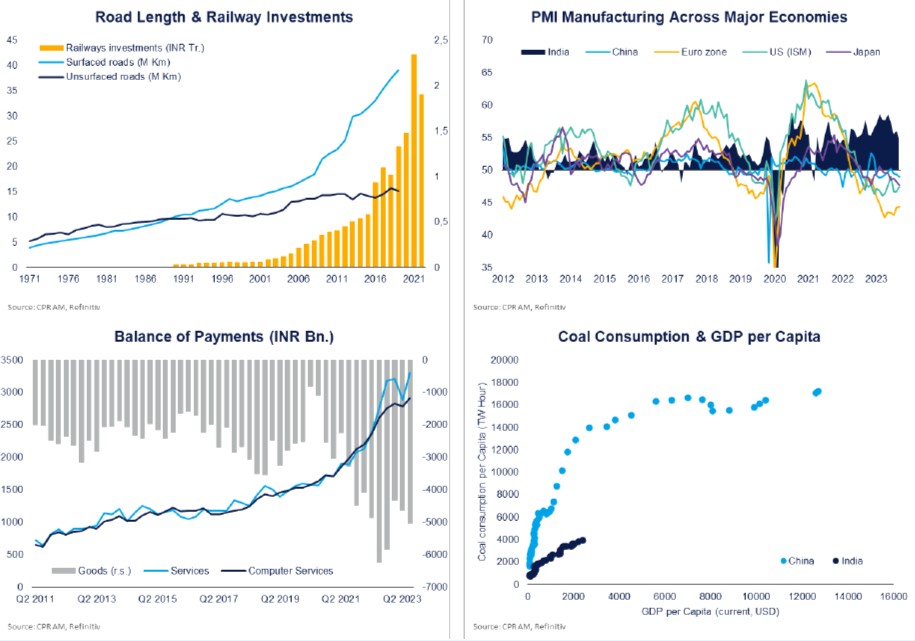

India’s GDP growth is particularly robust and has even accelerated in recent quarters. It is projected by its central bank at 7% this year. The IMF expects it to stabilise at between 6.5% and 7% in the coming years – far above the other large economies. The Indian economy draws its strength from a combination of several structural factors (demographics, stage of development, and major reforms) and from the effectiveness of its economic policy in recent years. By implementing massive plans (in infrastructures and digitalisation), the government has allowed investment to offset lacklustre growth in consumption and, ultimately, to stabilise growth at high levels. In the medium term, the receding of inflation and future monetary easing are likely to boost domestic demand and create the necessary balance between public and private sectors. India is also expected to continue expanding its international footprint, as seen in its announced target of tripling its exports by 2030.

Below, we detail these strengths, while drawing as clear a line as possible between the megatrends at work and more cyclical factors. And without throwing any doubt on this rosy scenario, we will also point out the weaknesses of the Indian economy, such as its job market, and its heavy exposures to commodity prices and to climate risk. Note also that despite its economic strength, India’s per capita GDP is still low compared to other economies.

Moreover, Indian society remains highly inegalitarian (the literacy rate is just 76%) and highly fragmented (there is just a 36% likelihood that two persons chosen at random will speak the same language).

“Make in India” or a new China?

Launched in 2014, the “Make in India” initiative is one of the hallmarks of Modi’s proactive economic policies. It aims to boost manufacturing output, reduce dependence on imports, and attract foreign investment. “Make in India” has moved up to the next level recently, as many companies plan to diversify their supply chains. This switch to a so-called “China +1” approach has featured several headline-making announcements, such as the new battery production capacities of Apple and its supplier Foxconn – an investment pegged at $1.5bn.

Through proactive policies, Indian authorities have in the past decade laid the foundations of this success with broadbased reforms, such as the Goods and Services Tax, which aim to formalise, unify and simplify the economy. Massive public investments have been deployed in tandem in order to modernise India’s infrastructures (via the National Logistics Policy), which are a long-standing obstacle to its competitiveness. In addition to these underlying efforts, the Production-Linked Incentives (PLI) initiative in place since 2020 has targeted accelerated development of 14 key sectors, including autos, pharmaceuticals and renewable energies. Beyond significant job creations, this industrial policy is meant to consolidate India’s bourgeoning role in global trade. To wit: Indian authorities are aiming to triple exports of goods and services by 2030.

But despite official efforts to boost the manufacturing sector, the Indian economy is still focused on services. Moreover, a Chinese-style development model (commodity-intensive and environmentally damaging) is not viable in India, especially as foreign investments are unlikely to come anywhere near those that China attracted in the past. And, lastly, India’s societal structure and administrative rigidities (albeit less stringent now) do not favour the development of mega-factories, as is the case in China. So, while India is unlikely to become “the next China”, its in-depth transformations suggest that it will gradually become more diversified and more integrated into the global economy.