How the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics sheds light on the major macrofinancial issues of our time

This year's Nobel Prize in Economics1 was awarded to economists Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, for "explaining how economic growth can be driven by innovation". Here we come back very briefly to the work of these economists and to the way in which they shed light on the major macrofinancial issues of the moment, and in particular the impact of Artificial Intelligence on growth.

Published on 20 October 2025

Joel Mokyr and the Interaction Between "Macro-Inventions" and "Micro-Inventions"

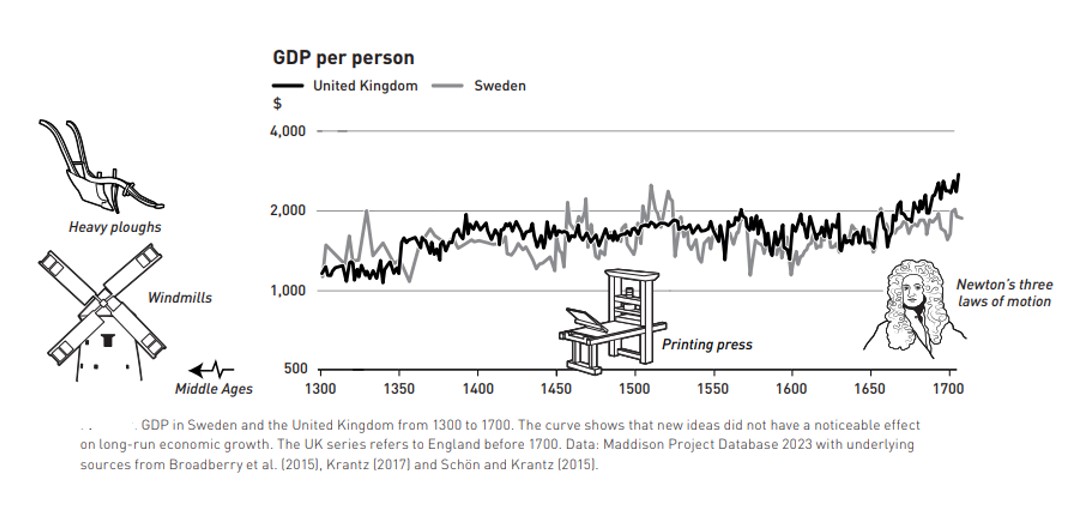

Joel Mokyr is a specialist in the history of economics. In particular, he used historical sources to study the conditions that allowed or did not allow technological innovations to trigger a continuous phase of economic growth through the ages. In a series of publications2, Joel Mokyr has shown that the interaction between science and applied technologies is crucial, and that the impact on economic growth depends on the translation of scientific advances into concrete applications that can be used by a large number of people.

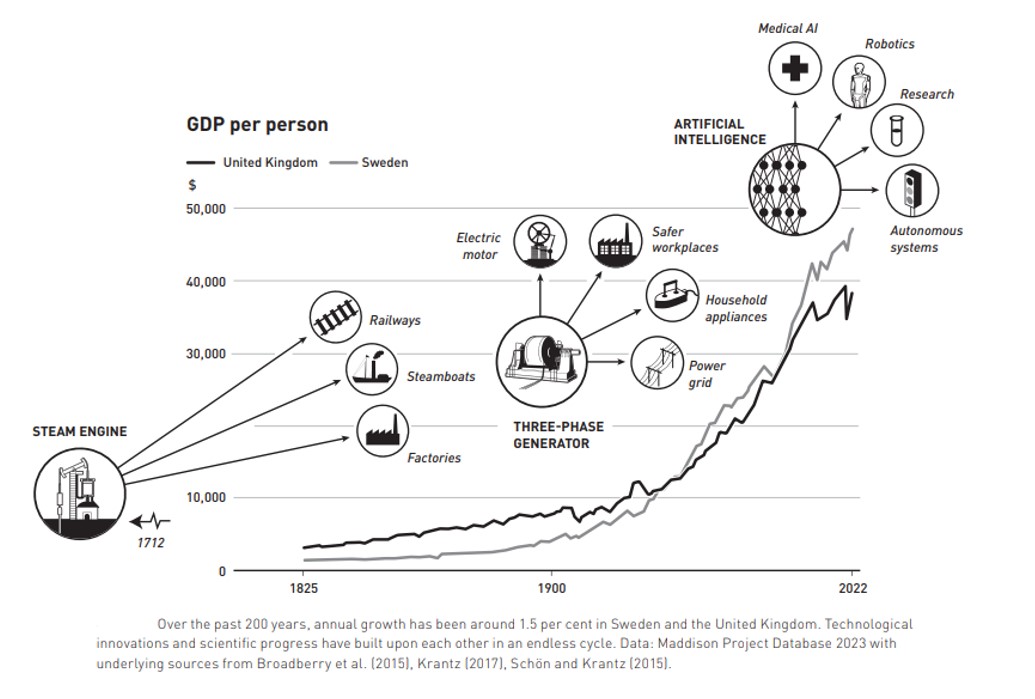

Mokyr thus distinguishes between "macro-inventions", which correspond to radical technological discontinuities determined by a leap in understanding, and "micro-inventions", which are closer to everyday life, which correspond to incremental improvements in existing technologies and make it possible to make the link between technology and economy. According to him, it is the ability to set up a virtuous circle between "macro-inventions" and "micro-inventions" that makes it possible to stimulate economic growth in a prolonged way. The Siècle des Lumières3, for example, was characterized by great scientific advances, but these did not materialize in applications that allowed economic activity to grow for a long time. Mokyr explains that this is what differentiated them from the industrial period (i.e. from the beginning of the nineteenth century), when Western economies began to grow for a long time.

This work is particularly relevant today since the progress of Artificial Intelligence (AI) models, in particular generative AI, has been spectacular in recent years, which could be akin to a "macro-invention". As the use of AI gradually spreads throughout the economy, one of the challenges of our time is to what extent companies will be able to benefit financially from it in their own fields of activity and therefore whether AI will succeed in sustaining economic growth.

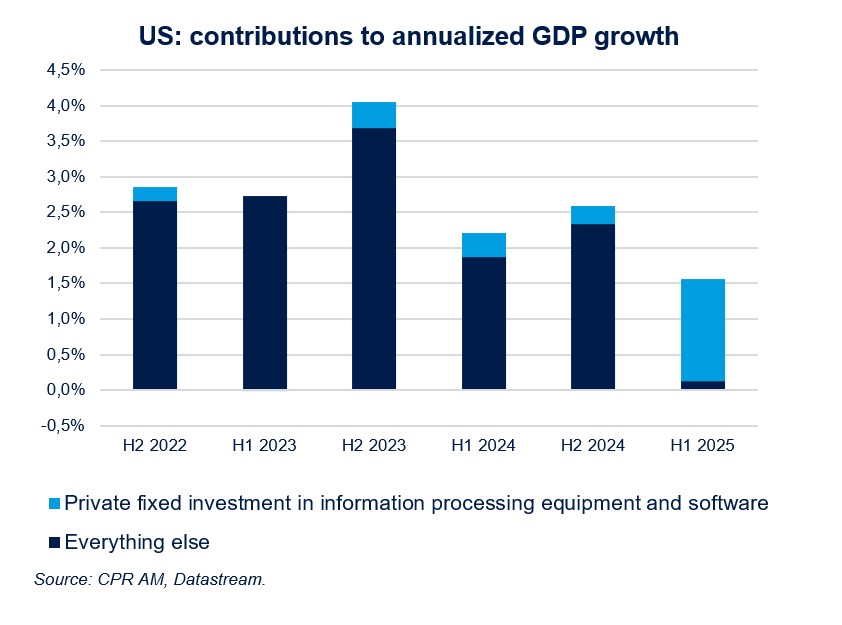

In the first half of 2025, private investment in software and computer equipment increased very sharply in the United States and made it possible to "save" growth: this acceleration was so strong that this segment, which represents 4% of US GDP, actually explains 92% of growth in the first half of the year. Some of the most advanced electronic chips used to train Artificial Intelligence (AI) models are classified in this category. Even if we have to take into account the fact that a good part of these investments are made with imported equipment (and that the "real" contribution is therefore less), we can see here that the investment cycle related to AI is now having a significant macroeconomic impact. Similarly, the momentum in data center construction continues to be very strong (+28% year-on-year in the United States in June) with the global cycle of Artificial Intelligence (AI) deployment.

This is likely to continue as there are many investment announcements, particularly from tech giants. In the case of the United States, spending on data center construction should soon surpass that on traditional office construction if trends continue. More generally, the contraction in non-residential construction spending would have been twice as sharp without data centers in the first half of 2025. In other words, the data center construction cycle partially limits the slowdown in the U.S. economy. One of the crucial points for the next few quarters is whether the United States will be able to produce enough electricity to support the construction of data centers.

Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt and "destructive creation"

For their part, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt are theorists who have built a mathematical model based on the idea of "creative destruction" proposed by Joseph Schumpeter more than 80 years ago. This concept is relatively simple: when a new and better product comes to market, companies selling older products go into decline. Thus, innovation is both a source of creation and destruction, with the emergence of winners and losers. In the paper for which they are awarded4, Aghion and Howitt point out that firms that innovate are motivated by the prospect of monopoly rents that they can capture once their innovations are patented, but that these rents will be destroyed by subsequent innovations. Their work suggests that sectors in which creative destruction processes are most intense contribute more to economic growth, which has subsequently been empirically validated.

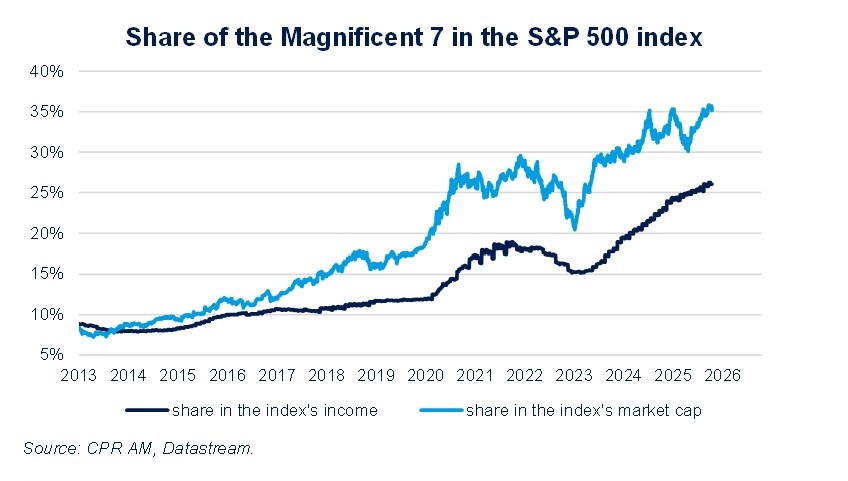

Here too, this work is very current. Over the past few years, a few highly innovative digital companies, mainly American, have experienced extraordinary growth and success, each in its own specialty. These companies each dominate segments of the digital economy in their own way, and some sometimes find themselves in a situation reminiscent of the monopoly described by Aghion and Howitt. This happened when competition in the United States weakened sharply in the twenty-first century in most sectors5. As a result, during the 2010s, they gradually became the largest market capitalizations in the United States. Apple became in 2018 the first company in the world valued at more than $1,000 billion, in 2020 the first at $2,000 billion, in 2023 the first at $3,000 billion and it was Nvidia that became the first to be valued at more than $4000 billion in 2025.

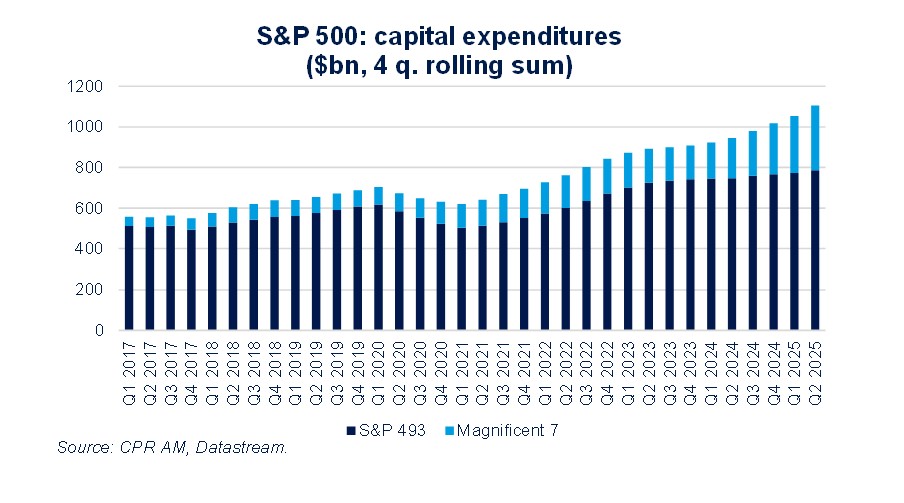

One of the methods used by these tech companies to increase their market share and avoid being disrupted themselves has been to buy smaller, younger companies, before they become rivals6. It must be said that concentration in the digital market can have advantages related to "network effects": the larger the network, the greater the likelihood that participants will be able to interact with each other. But concentration can also lead to significant disadvantages (possibility of price increases, reduced choice, lower quality, ultimately less innovation, etc.). In any case, the theory formulated by Aghion and Howitt sheds light on the mechanisms that have led to the increasing concentration observed in the stock markets in recent years: the Magnificent Seven now represent about 35% of the capitalization of the S&P 500. The consequences are macroeconomic since the Magnificent Seven, motivated by the fact of maintaining their competitive advantage, have been at the origin of more than 77% of the capital expenditures of S&P 500 companies over the last 18 months.

The work of the economists awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics, even if it sometimes dates back several decades (as is customary for this type of award), provides a better understanding of the major macrofinancial issues of our time, and in particular the dynamics of innovation related to Artificial Intelligence (AI).

The speed of diffusion of innovations has varied greatly since the nineteenth century, but that of AI is one of the fastest ever observed. In an ageing world, the impact of AI on economic growth is a central issue and the three recipients of the 2025 Nobel Prize are quite optimistic on the subject. In any case, it is absolutely essential to always try to take a step back from the phases of technological change.

This award is particularly appreciated by CPRAM, a specialist in thematic investment, which has made the identification and study of technical and scientific innovations a key element of its management.

1 - More specifically, the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economics.

2 - Mokyr, J. (1990). The lever of riches: Technological creativity and economic progress. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press. Mokyr, J. (2002). The gifts of Athena: Historical origins of the knowledge economy. Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.: Princeton University Press.

3 - The Enlightenment: name given to the 18th-century intellectual movement in Europe that emphasized reason, science, and individual rights over tradition and authority

4 - Aghion, Philippe, and Peter Howitt. 1992. "A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction." Econometrica 60, no. 2: 323-351.

5 - See the book The Winners of Competition: When France Does Better Than the United States by economist Thomas Philippon.

6 - See the recent paper Jin G., M. Leccese, L. Wagman and Y. Wang, 2025, "Serial acquisitions in tech", NBER working paper n°34178.