2024 assessment of the monetary easing cycle

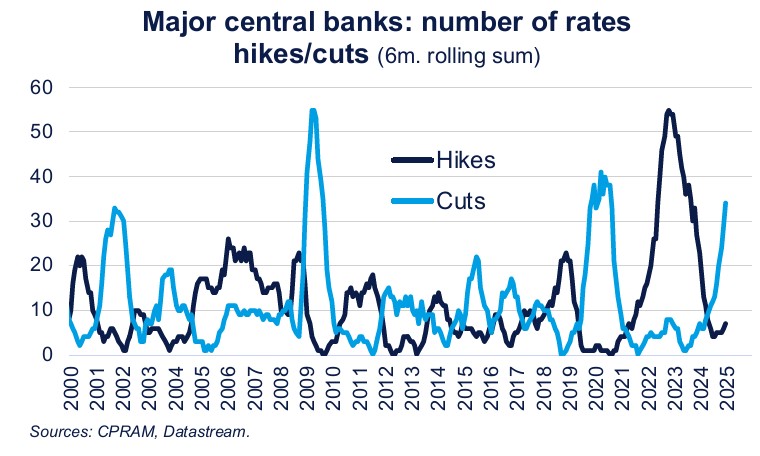

In 2022 and 2023, high inflation pushed the world’s major central banks to undertake a phase of monetary tightening that is often considered the most aggressive since the early 1980s. In 2024, we have seen a global movement of monetary easing, with a number of rate cuts in the major economies roughly equivalent to that observed during the covid period. As the year has just ended, we thought it was appropriate to take stock of it.

Published on 3 January 2025

Juliette Cohen

Strategist - CPRAM

Jean-Thomas Heissat

Strategist - CPRAM

Bastien Drut

Head of Research and Strategy - CPRAM

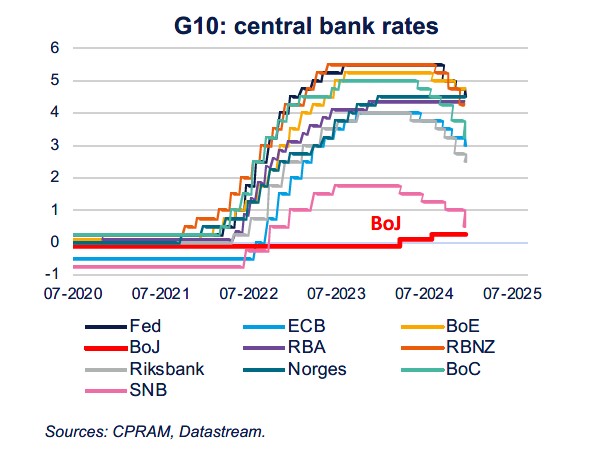

Interest rates remain high in developed countries despite cuts

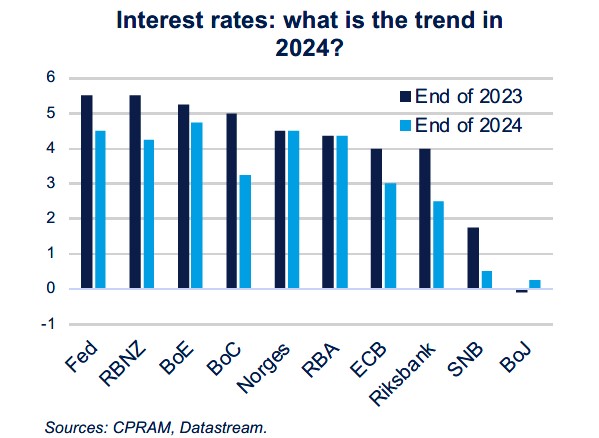

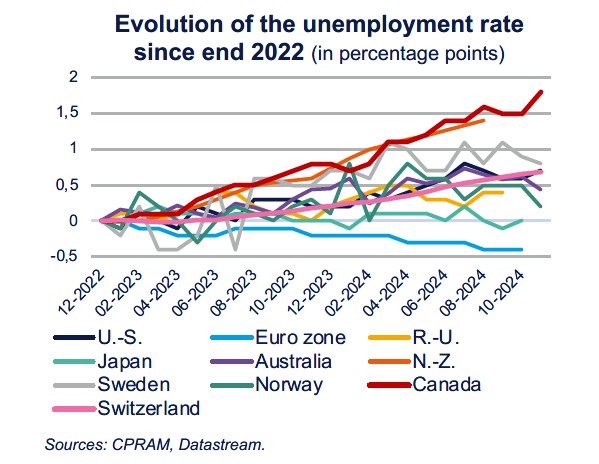

2024 marked the beginning of the cycle of rate cuts in most developed countries, but this was done in a dispersed way, in terms of both pace and magnitude. The central banks that cut their key rates the most were, in order, those of Canada, Sweden, Switzerland and New Zealand (cumulative cuts of 175, 150, 150 and 125 bps respectively in 2024), where the economic situation was particularly affected by the monetary tightening cycle of 2022-2023 and where the unemployment rate increased the most. That said, even for the developed central bank that cut rates the most, the Bank of Canada (BoC), which cut its rate from 5% to 3.25% in 2024, rates remain higher than over the entire period from 2009 to 2022.

The ECB made 4 rate cuts of 25 bps over the year 2024 and lowered its deposit rate from 4% to 3%, although the euro area is the only developed area where the unemployment rate fell over the period 2023-2024. The Fed only began its rate cut cycle in September (with a 50 bps rate cut) but it lowered its rates as much as the ECB over the year (100 bps), by reducing its target range for fed funds from 5.25/5.50% to 4.25/4.50%. In December, the Fed indicated, after only three rate cuts, that it would enter a new phase in its rate cut cycle. Indeed, the recent halt to disinflation and the uncertainties related to the policies of the future administration will push the central bank to be much more cautious. It will only lower rates again in the event of further tangible progress on the inflation front. In developed countries, only a few central banks have not lowered their key rates:

- In Norway, where Norges bank has not lowered its rates (4.50%) due to the historically low levels of the currency;

- In Australia, where the RBA has not lowered its rates (4.35%) because inflation did not converge to its target range of 2 to 3% until Q3 2024;

- In Japan, where the BoJ, well behind its counterparts, has raised its key rates twice, which remain (as a reminder) still lower than those of other developed countries.

Ultimately, the central banks of developed countries have only "undone" around 20% of the key rate hikes that were made in 2022-2023 and key rates remain overall significantly higher than before covid.

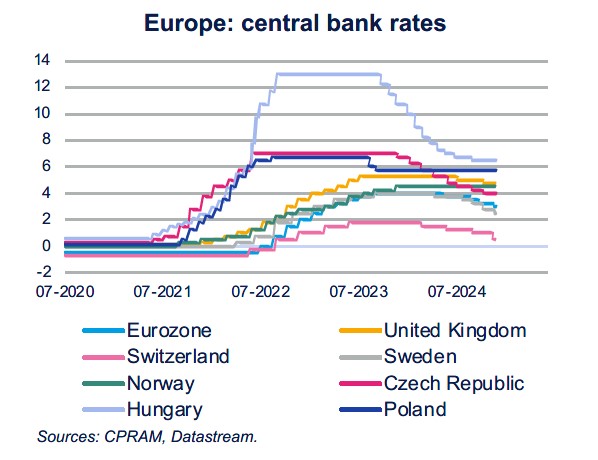

In Europe, rate cuts everywhere except in Norway and Poland

In Europe, all central banks have lowered their rates, except in Norway and Poland. The Swiss National Bank (SNB) was the first G10 central bank to lower its rates, in March 2024. It then made 3 other cuts to bring its key rate to 0.50% in December 2024, a level that is considered below the neutral rate (1%) by former governor Thomas Jordan. The SNB says it is considering further rate cuts in a context characterized by low inflation (0.7% in November 2024), falling inflation forecasts for 2024 and 2025 with deflationary pressures linked to a strong Swiss franc.

The ECB started its rate cut cycle in June 2024. It initially acted cautiously, pausing in July 2024 and reiterating its reliance on data. However, the ECB gradually gained confidence in the disinflation process and paid more attention to weak growth, leading it to act at each Council meeting from September. For 2025, rate cuts should continue at the same pace in the first half of the year. The issue of the neutral rate has not been addressed by the ECB so far, given the road ahead, but will be at the heart of the debates in 2025. In parallel with the rate cuts, the ECB continued its quantitative tightening on the APP and then PEPP securities portfolios, which led the financial markets to absorb significantly larger quantities of sovereign bonds.

The Bank of England (BoE) started its rate cut cycle in August 2024 and made a second rate cut in November, bringing its key rate to 4.75%. While the first phase of disinflation was rapid thanks to energy prices and led to inflation reaching 2.3% in October, the focus remains on very high inflation in services (5%) and very strong wage growth. In this context, the BoE was one of the most cautious developed central banks and opted for the status quo in December. It believes that monetary policy must remain restrictive long enough for inflation to return sustainably to target.

In the Nordic countries, the Riksbank in Sweden and the Norges bank in Norway have taken opposite paths, with the former proceeding with aggressive monetary easing (since May 2024, it has lowered its key rate from 4% to 2.50%) while the Norges bank has left its key rate unchanged for the year 2024 at 4.5%. Both intend to proceed with a rate cut in the first quarter of 2025.

In Eastern Europe, the Czech and Hungarian central banks have made significant rate cuts (respectively by 275 and 425 bps over the year) but from higher initial levels and their key rates were respectively 4% and 6.5% at the end of 2024. The Polish central bank (NBP) has kept its rates unchanged at 5.75%.

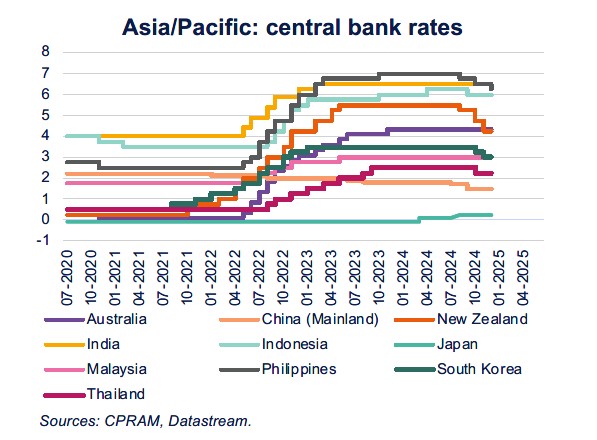

In Asia, the Chinese and Japanese central banks are each going against the tide in their own way

The monetary environment is not very homogeneous in Asia due to marked country specificities, and in particular the asynchronous nature of the trajectories of China and Japan vis-à-vis other economies.

In China, the PBoC has thus continued to ease its monetary policy in order to support an economy weakened by 3 years of real estate crisis. It should be noted that unlike most central banks, China, spared by the inflationary shock, had not raised its key rates since 2018. As early as Q1 2024, the PBoC lowered the required reserve ratio applied to banks, before doing so again at the end of September. Several key rate cuts were announced in the second half of the year, and others are expected in the short to medium term. The explicit shift towards an accommodative monetary policy (unprecedented since the 2008 crisis) was also confirmed by the Politburo in December. In addition, significant adjustments to the framework and tools of Chinese monetary policy were also put in place in 2024. Beyond monetary policy, the PBoC has retained a central role in the implementation and coordination of measures to support the economy (real estate, banking, stock market, etc.).

In Japan, the BoJ took advantage of the return of inflation to end a prolonged period of ultra-accommodative policy, while almost all developed central banks began a cycle of rate cuts. The BoJ began this new phase of normalization in March 2024 with a first rate hike and proceeded with a second hike, which caused significant market turmoil, at the end of July. Admittedly, the key rate remains very low in absolute terms (0.25%), but these levels have not been seen since 2008. The balance sheet policy has also been significantly adjusted over the year through the reduction of asset purchases and the implementation of the balance sheet reduction program. 2024 therefore marked a real turning point for the BoJ, which will likely continue to sail against the tide in the coming quarters.

Elsewhere in Asia, central banks have generally started to ease their monetary policies, thus echoing the trajectories followed by developed countries. Some have decided to announce initial cuts ahead of the Fed, such as New Zealand (125bps cut in total) or the Philippines (50bps cut in total). Others have been more cautious (Indonesia, Thailand, South Korea), in particular to limit pressure on their respective currencies. Some central banks, however, are exceptions by maintaining restrictive policies. This is particularly the case for the RBI in India (6.5% since February 2023) but also the RBA in Australia (4.35% since December 2023), with both economies still facing inflationary pressures. However, these laggards should be forced to fall into line in 2025.

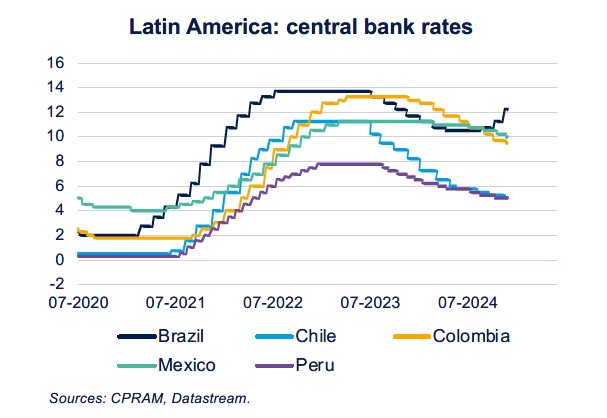

In Latin America, Brazil is once again in a tightening phase

Latin America is the area that was a forerunner in the monetary easing movement with rate cuts starting in the summer of 2023. In this zone, the Chilean and Colombian central banks lowered their key rates sharply in 2024, i.e. by more than 3 percentage points, to end the year 2024 at 5% and 9.5% respectively. The Mexican central bank was much more cautious over the year, lowering its rates by only 125 bps to 10%: for this country, the future policies of the Trump administration will be decisive in 2025. Finally, the Brazilian central bank (BCB) stood out in the second half of 2024 by stopping its easing cycle and returning to rate hikes due to the reacceleration of inflation and inflation expectations. New rate hikes of 100 bps are envisaged for the coming months.

In conclusion

- Central banks in developed countries have “undone” only about 20% of the policy rate hikes that were made in 2022-2023 and policy rates remain significantly higher overall than before covid. This is still a drag on economic activity at the global level;

- After only three rate cuts, the Fed has already entered a new phase of its easing cycle and will only cut rates again if there is further tangible progress on the inflation front;

- After 100 bps of rate cuts in 2024, the ECB is expected to continue to cut rates and move closer to the “neutral rate”;

- The PBoC is expected to continue to ease monetary policy in 2025 to counteract the weakness in the economy in the wake of the housing crisis;

- Unlike the vast majority of central banks in the world, which have started or continued their monetary easing, the BoJ has started a historic cycle of rate hikes in 2024, but the amplitude is limited and the outcome uncertain;

- Several central banks that remained on pause in 2024 (Australia, Norway, India) are expected to start their rate cut cycle in 2025;

- The Brazilian central bank stands out within the G20 as the only one to have returned to a tightening cycle in 2024 due to a reacceleration of inflation and inflation expectations.