A new golden age for gold?

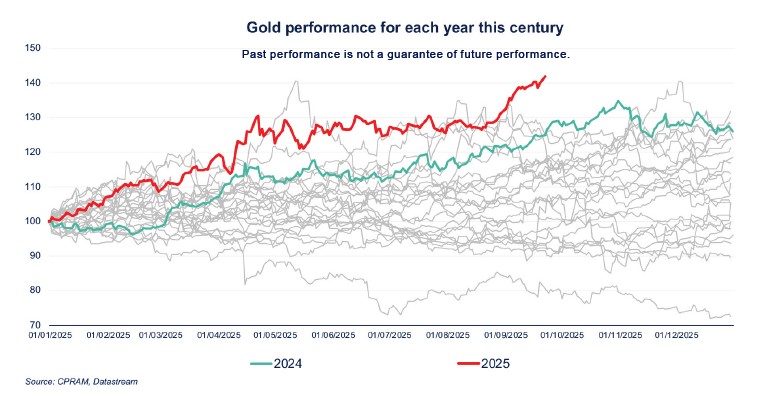

For the time being, gold is having its best year since the beginning of the century. Several structural factors are behind this sharp rise in gold prices: fears about public debt trajectories, a trend towards de-dollarisation, fears about the independence of central banks, geopolitical uncertainties, etc. In reality, it seems that a new golden age of gold is coming... And exposure to mining companies makes sense against this backdrop.

Published le 25 September 2025

Gold, a very old monetary use

For millennia, precious metals have been used as currency. From the nineteenth century, banknotes, convertible into gold or silver, began to circulate and following several crises, central banks obtained a monopoly on the issuance of these banknotes: they had to hold a reserve of gold and silver capable of ensuring total coverage of the banknotes they issued. They were thus in charge of managing the gold standard system, under which states set the value of their currency in a fixed quantity of gold. When their gold reserves dwindled, they raised their discount rates (the rate at which they lend to other banks) to encourage the inflow of international capital and thus gold.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, central banks were relatively independent of governments, but the latter's interference in the policies of the former was stronger during periods of war and crisis. For example, when the First World War broke out, the gold standard system was suspended and governments relied heavily on central bank money to finance war and reparations spending, leading to periods of hyperinflation in some cases. This system was reintroduced for a few years after the end of the First World War. At the end of World War II in 1944, the Bretton Woods agreements instituted that only the US dollar would be pegged to gold and other currencies would be pegged to the US dollar.

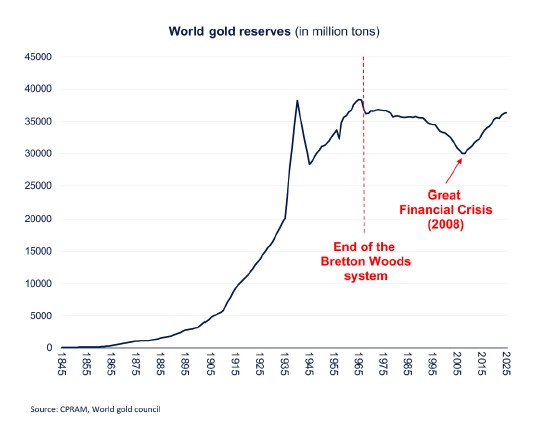

The deterioration of the United States' balance of payments and the decline in the country's gold reserves led Richard Nixon to announce on August 15, 1971 the end of the convertibility of the dollar into gold, thus putting an end to the Bretton Woods system. With gold suddenly losing its centrality in the international monetary system, central banks had stopped accumulating gold as they had done for more than a century and began accumulating foreign currency assets instead. The volumes of gold held by government entities have been slowly but steadily declining for nearly 40 years.

A recent revival of central bank interest in gold

Global gold reserves have been on the rise since the 2008 financial crisis and have even reached their highest level in more than 40 years in 2025. The recent rate of accumulation is reminiscent of that of the early twentieth century.

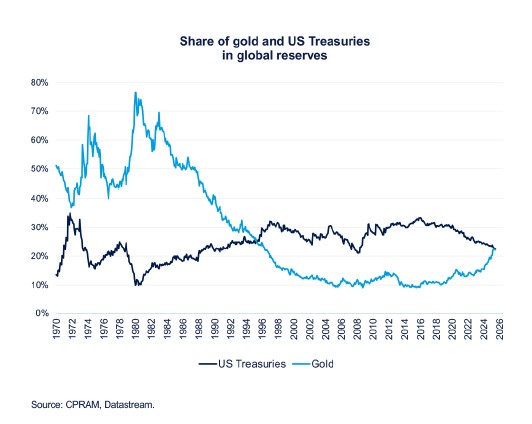

The academic literature1 has identified several reasons why central banks may hold gold, some of which have recently found renewed interest. Firstly, gold has the advantage of not having an intrinsic risk of default, while the public debt of Western countries, which represents the basis of foreign currency-denominated assets, is now very high and continues to rise. Recent concerns about the state of public finances in large countries may have led central banks and investors in general to weigh gold more heavily in relation to sovereign bonds. In addition, gold holdings have the advantage of not being subject to political manipulation, unlike government debt securities and foreign currencies. This has been particularly evident since 2025 and concerns about the loss of central bank independence. In addition, the geopolitical context has also reinforced the relevance of holding gold for a number of countries in recent years. An IMF working paper2 also showed that several countries increased their gold holdings when the likelihood of international sanctions increased. Finally, the fact that the Trump administration has announced in 2025 that it wants to massively reduce the US trade deficit is likely to weaken the US dollar's status as the dominant currency and the fact that it has no credible replacement reinforces the attractiveness of gold for the reserves of many governments.

All these reasons contribute to the fact that gold has taken a larger share of global reserves in the course of 2025 than US Treasury securities, which has not happened since the 1990s.

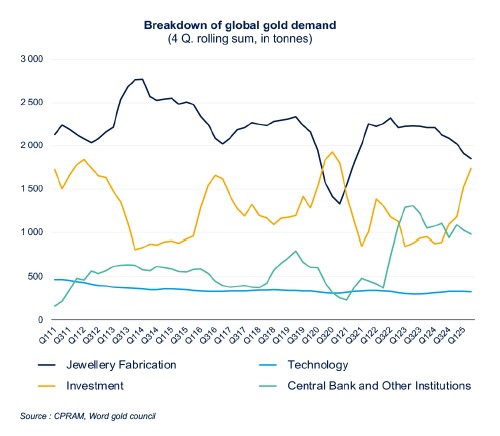

Other contributions to the gold demand

Central banks are not the only players buying gold, far from it. The main source of demand for this metal comes from the manufacture of jewellery, but this demand has been rather stable over the past decade. There is also a demand for gold from the industrial sector, particularly from clean technologies, but this remains marginal. Finally, gold is also used for investment purposes. In this context, an argument often put forward is that gold can be used as a hedge against inflation risk over long periods of time and as a safe haven in situations of particularly high uncertainty. Here too, this reason for gold holdings has become even more relevant in 2025 with the uncertainty related to the effect of the increase in tariffs on inflation. Finally, gold generally appreciates in flight-to-quality phases and is a complementary way for Treasury securities to hedge against rising risk-off phases.

Investment in listed mining companies, a relevant exposure to gold?

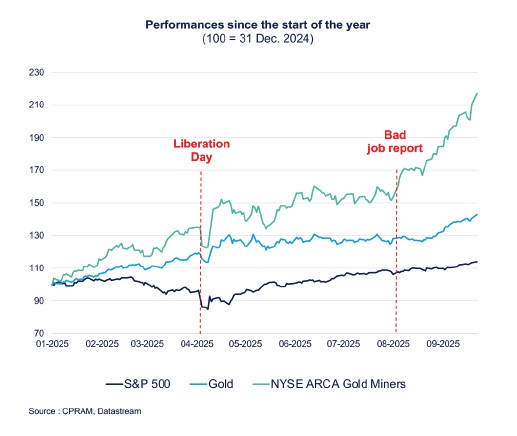

It is clear from the above that exposure to gold can offer very attractive returns. However, the purchase of physical gold by UCITS funds is very constrained and investing in listed mining companies offers a relevant alternative. This was particularly the case in 2025 when the NYSE ARCA Gold Miners Index, which includes the main listed companies operating in gold mining, saw its value more than double while gold rose by around 40% and the S&P 500 by 13% (returns as of mid-September).

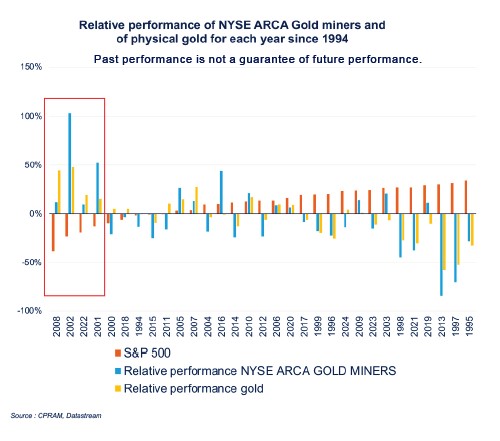

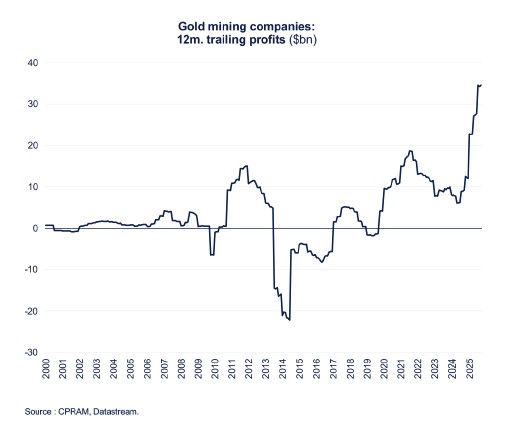

As an asset class, mining companies have the particularity of incorporating the characteristics of the gold market, but also of the global equity markets. If we observe over the long term a performance lever of mining companies of 2 to 3 times compared to gold, the latter, as companies, are also exposed to the same problems as others. Thus, the underperformance of gold mines between mid-2020 and the end of 2024 is directly linked to cost inflation, which has not spared this industry, thereby impacting operating margins. It was not until mid-2024 that the sharp rise in gold prices made it possible to offset this inflationary effect.

Observers also sometimes fear that mining companies will behave more closely to equity markets than to physical gold in the event of a financial crisis and that they will not benefit from the rise in gold, a traditional safe haven, in these situations. This phenomenon can indeed be observed often in the event of a sharp increase in volatility, but over short periods. An analysis of the past 30 years shows that the NYSE ARCA Gold Miners Index has significantly outperformed the S&P 500 in years of sharp declines in stocks, but also outperformed physical gold in some of those years. In addition, one of the notable characteristics of mines, like gold, is their very low correlation with other asset classes, which makes them particularly interesting from a portfolio diversification perspective.

Despite their recent sharp rise, the performance of gold mines still lags behind gold in terms of performance. Thus, they only recovered at the beginning of September 2025 their record of September 2011, when gold prices did not exceed $1900 per ounce. Thanks to the levels reached by gold prices in recent months, operating margins in the gold industry are at historic levels, allowing for unprecedented cash generation, and therefore significantly improved earnings expectations. This new situation is far from being reflected in the low level of mine valuation, which still offers significant appreciation potential.

In conclusion, exposure to mining companies seems to be complementary to exposure to physical gold in the context of equity risk diversification.

1. See, for example, the synthesis by Zulaica O., 2020, "What share for gold? On the interaction of gold and foreign exchange reserve returns",

BIS working paper n°906.

2. Arslanalp S., B. Eichengreen B. & C. Simpson-Bell, 2023, “Gold as International Reserves: A Barbarous Relic No More?”, IMF working paper.

Warning

Investing involves risks, including the risk of capital loss. Past performance is not a guarantee or an indicator of future performance. This communication is not contractual in nature but constitutes advertising communication. It is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation, analysis, or financial advice. Furthermore, it should not be considered as a solicitation, invitation, or offer to buy or sell collective investment schemes (CIS). Before subscribing to a collective investment scheme (CIS), the potential investor is advised to consult their advisor so that the latter can ensure the suitability of the intended investment with their financial and patrimonial situation. This document is based on sources that CPRAM considers reliable at the time of publication. Data, opinions, and analyses may be changed without notice. CPRAM disclaims any direct or indirect liability that may result from the use of the information contained in this document. CPRAM cannot in any case be held responsible for any decision or investment made based on the information contained in this document. The information contained herein may not be copied, reproduced, modified, translated, or distributed without the prior written permission of CPRAM. All trademarks and logos used for illustration purposes in this document are the property of their respective owners. This publication may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, or communicated to third parties without the prior authorization of CPRAM.

This publication is not intended for US persons as defined in the US Securities Act of 1933. MSCI information is exclusively intended for your internal use, may not be reproduced or redistributed in any form, and may not be used as a basis or component of a financial instrument, product, or index.

All registered trademarks and logos used for informational purposes are the property of their respective owners.

Subject to compliance with its obligations, CPRAM cannot be held liable for financial or any other consequences resulting from the investment. All regulatory documentation is available in French on the website www.cpram.com or upon simple request at the management company's headquarters.