European ambitions to combat climate change

Now that the European Commission has just set a new 2040 climate target for the European Union, this looks like a good time for an update on the decarbonation of the European economy and for a progress report on the European Green Deal.

Published on 8 April 2024

How far along is the decarbonation of the European economy?

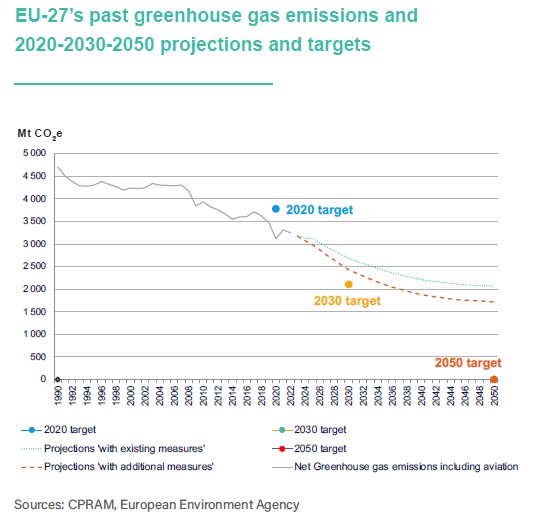

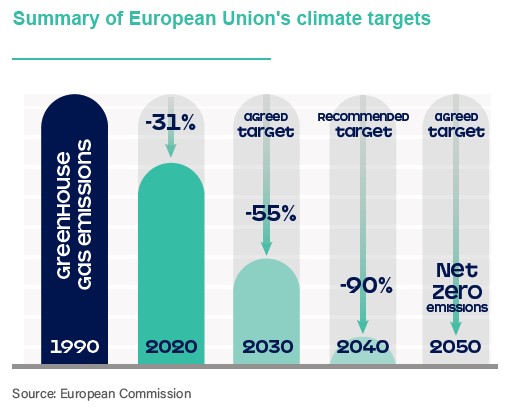

European countries were supposed to have reduced their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 30% by 2020 compared to their 1990 levels. According to figures from the European Environment Agency (EEA), they did indeed meet this target by 2020. However, as Covid made 2020 an unusual year, a more meaningful benchmark is 2022, once the economy had returned to normal. With a 31% reduction in emissions between 1990 and 20221, the EU hit the 2020. It was able to do so thanks to shifts in energy generation methods, particularly a significant reduction in the use of coal and progress in renewable energy use. On top of these, there was a slight decrease in total energy consumption and substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions from manufacturing.

What comes next?

Under the European Climate Law, member-countries have pledged to reduce their GHG emissions by 55% by 2030 vs. their 1990 levels. This target looks even more ambitious as it would require tripling the current average annual absolute GHG reductions between now and 2030 in comparison with the past 10 years. The EEA plans to monitor progress annually under the European Action Programme (EAP) between 2023 and 2030.

As of the end of 2023, it estimated that there was a rather high likelihood of approaching the 55% GHG emissions reduction target by 2030. Current policies point to a 48% reduction (based on the “with existing measures” scenario).

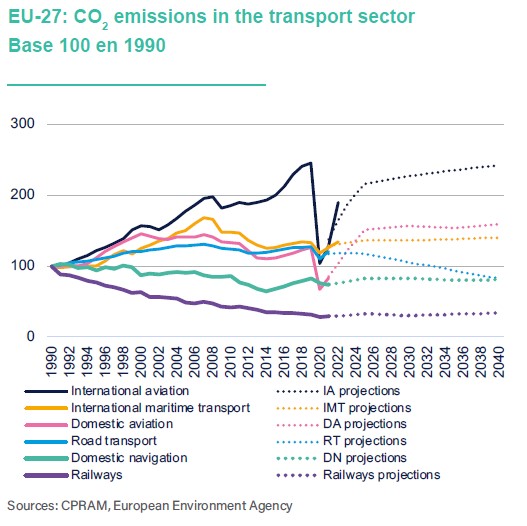

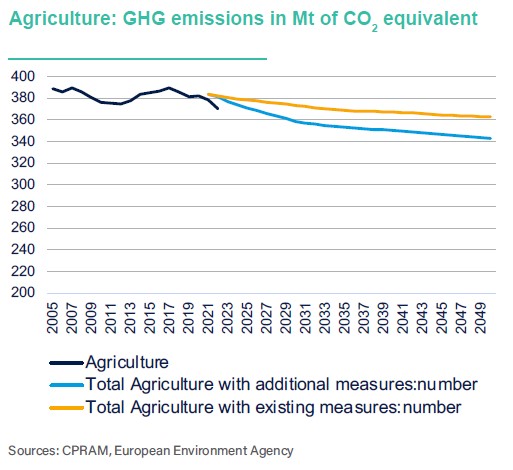

In its end-2023 report, the EEA estimated that the construction sector could continue to make a major contribution in coming years. There is also room for improvement in agriculture and transport, given their modest progress in recent years. These two sectors lowered their emissions by 4.7% and 4.5%, respectively, from 2005 to 2022, vs. an almost 15% average reduction by European sectors subject to emissions-reduction targets.

In transport, EEA projections show that road transport alone will manage to reduce its emissions in coming years, thanks to the development of electric vehicles (EVs). However, emissions are expected to rise in domestic and international air transport and in seaborne transport.

In agriculture, national policies currently in place in the EU are likely to lead to a reduction of just 1.5% in farming emissions between 2020 and 2040. If currently planned policies and measures are implemented, a slightly higher reduction of 5% is possible. Even that figure is far from the EU’s overall objectives. Underdevelopment of organic farming is one of the areas where Europe is far behind and where there’s room for improvement. The agro-food sector is also being called on to reduce the waste that it produces and to enhance its product lifecycles.

A new 2040 target in view of 2050 carbon neutrality

In early February, the president of the European Commission, Ursula Von der Leyen, submitted the EU’s climate target proposal for 2040, at an intermediate point between the 55% reduction in GHG emissions targeted for 2030 vs. 1990 levels and the 2050 carbon neutrality target. Based on the recommendations of the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change (ESABCC), it proposes that the EU set a target of reducing its GHG emissions by 90% by 2040. This proposal is a starting point for discussions, and the actual target will have to be approved at the next European Council meeting. According to the Commission’s working paper, this would require that “the 2030 framework be passed in full”, meaning all Green Deal legislation, but it also stresses the need to preserve the competitiveness of European industry and for a fair transition that benefits everyone.

In all three scenarios for meeting the 2040 target, the Commission’s working document cites the need for massive investments in the energy sector.

The Green Deal: paused or shut down?

The European Green Deal was launched in 2019 to guide the EU’s environmental transition towards carbon neutrality and had been presented as the EU’s new growth strategy. Since 2020, it has encompassed all new legislation sponsored by the European Commission. The European Union had set four priorities under the Green Deal: the environmental and digital transition of industry, the circular economy, protection of biodiversity, and energy systems.

The fact that it was launched in 2020 allowed it to access substantial financing, as more than one third of the funds under the Next Generation EU (€800bn) stimulus plan and one third of the EU’s multi-year budget funds had been earmarked for the climate transition.

After passage of about 30 new texts within a few months, some foot-dragging has emerged and have led to the postponement or rejection of several legislations. Several heads of state have called for a regulatory pause. The issue of European industry’s competitiveness on the international stage became more pressing with the spike in energy prices in 2022 and competition from Chinese EVs. The deployment of renewable energies has run into some serious obstacles arising from a less favourable economic environment, including higher financing costs, higher electricity costs, and a slowdown in activity. The European Commission’s reform ambitions have also been slowed by growing social unrest in certain sectors. And, lastly, disbursements under the Next Generation EU have been longer and more challenging than expected. Almost four years after launch, only about €200bn has been paid out to member-states, out of the plan’s €1000bn.

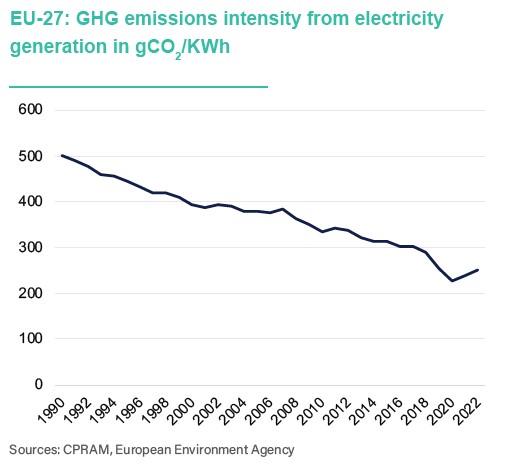

Energy is one of the sectors that has made the greatest progress in decarbonation. Emissions from electricity generation fell by 50% from 1990 to 2022. As a result, in 2022, 39.4% of electricity was generated from renewable energy sources, 38.7% from fossil fuels, and 21.9% from nuclear power. The October 2023 updating of the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) raised the 2030 renewable energy target to 42.5%, with member-states striving to reach 45%.

In the transport sector, the phase-out of new ICE cars by 2035 has been approved and should make it possible to decarbonate road transport.

In contrast, the Farm to Fork agricultural transition policy has unleased protests. Agriculture accounted for 10.7% of the EU’s GHG emissions in 2021 and is a major challenge in reducing the EU’s overall GHG emissions and for preserving biodiversity. Reform of the agricultural sector has been made even more challenging by many contradictory objectives, including ensuring EU food security, maintaining international competitiveness, keeping food affordable for European consumers, and helping to preserve biodiversity.

Several 2030 objectives will probably be missed, such as the 25% target for organic farming. The Sustainable Use Regulation (SUR), which aims to halve the use of pesticides by 2030, was rejected by the European Parliament in November 2023. Faced with these challenges and with farmer protests in several member-states, including France, the European Commission redirected its approach in this area to enhance dialogue between stakeholders, launching, for example, a strategic dialogue on the future of the EU’s food systems. Keep in mind also that the Common Agricultural Policy is one of the European main budget’s items, with $307bn set aside for 2023-2027.

European industrial policy is being hit by a weaker economy, and mainly by higher energy and financing costs. Manufacturing faces several structural technical changes, including the switch from ICE vehicles to EVs, the development of renewables, and increased use of hydrogen in some hard-to-decarbonate sectors. Granted, European financings have been set aside to assist this transition and to ensure European sovereignty in certain sectors deemed key for the climate transition, but disbursing funds remains a long and challenging process. Meanwhile, the regulatory framework that is still in place in some areas is an obstacle to deploying projects. Despite strong political will, the Net Zero Industry Act of 2023 has not yet had an impact as structural as comparable plans in China or the US.

The European Union met the climate targets it had set for 2020 and is still able to achieve its 2030 targets with a proactive and comprehensive policy. However, as decarbonation of the European economy moves forward, outstanding reforms are looking more and more structural and complex. They require more intensive dialogue and to achieve broad-based support they must take into account the reality of global competition. This makes the equation a bit more complicated, whereas climate change is already with us and requires urgent answers.

1. Total net greenhouse gas emission trends and projections in Europe, 2023. European Environment Agency.