Germany: towards a budgetary Revolution?

The budgetary announcements of the likely new German Chancellor, Friedrich Merz, mark a break with the extremely cautious attitude that prevailed over the past 20 years, and particularly during Angela Merkel's term. If they materialize, it would not be an exaggeration to speak of a budgetary revolution.

Published on 14 March 2025

Juliette Cohen

Senior Strategist - CPRAM

Bastien Drut

Head of Research and Strategy - CPRAM

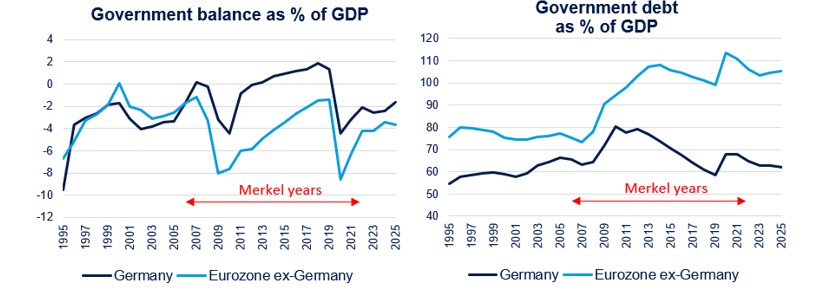

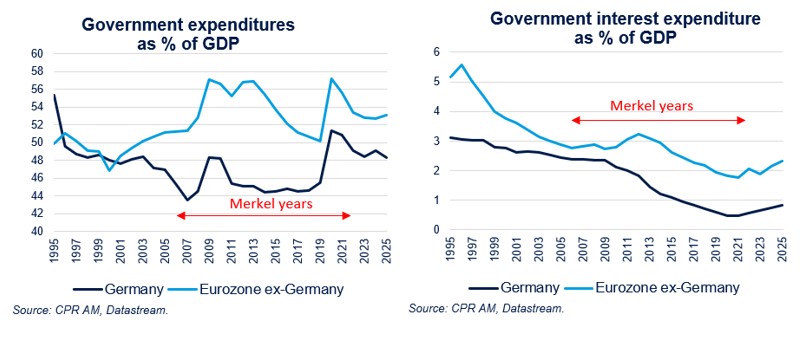

Fiscal Conservatism during the Merkel Years

Angela Merkel became Chancellor in November 2005 and remained in office until December 2021. Her 16 years in power were marked by formidable conservatism on fiscal matters: while the German deficit was, on average, slightly higher than that of other Eurozone countries before her arrival as Chancellor, it was significantly reduced thereafter, and the country even recorded budget surpluses for most of the 2010s.

After the particularly severe recession of 2009, the German authorities sought to rapidly consolidate their budgets and took some radical decisions. The debt brake rule, which limits the structural deficit to 0.35% of GDP, was adopted in 2009 and came into effect in 2011. Wolfgang Schaüble, Finance Minister from 2009 to 2017, was notably the custodian of fiscal orthodoxy with his famous "Schwarze Null" and maintained iron pressure on public spending. Furthermore, Schaüble notably demanded draconian austerity measures for Southern European countries during the sovereign debt crisis, which were likely counterproductive for these countries' public finances and increased the divergence with Germany.

Other factors have increased the divergence in public finances between Germany and other eurozone countries. While Germany was labeled "the sick man of Europe" in the early 2000s, labor market flexibility following the Hartz reforms adopted between 2003 and 2005 gradually led to more vigorous growth. Decentralization measures, the upgrading of industry, and integration with Eastern European countries are other factors cited to explain why Germany experienced stronger growth than its neighbors in the 2010s.

Finally, the eurozone crisis has permanently changed the way financial markets assess government credit risk: since the 2008 financial crisis, they have favored German bonds much more than those of other eurozone countries. As a result, German government interest expenditures have fallen more than those of other countries, increasing fiscal balance divergence and... thus the relative attractiveness of German debt.

Towards a sharp acceleration in spending under Merz?

The three years of Olaf Scholz's chancellorship, marked almost from the beginning by the invasion of Ukraine and the energy crisis, will likely have been just a transitional period. The coalition with the Greens and the FDP, a party very conservative in terms of budgetary policy, has precisely fallen apart due to disagreements over a possible easing of the budgetary golden rule. The fact that Germany has experienced zero GDP growth since the end of 2019 (see our recent article "Germany: 5 Years of Stagnation, and After?") and the geopolitical context have made the hypothesis of large public investments more relevant than ever.

The elections on February 23 put the CDU/CSU in the lead, which will govern in coalition with the SPD, and Friedrich Merz is expected to become the new chancellor. Very quickly, the CDU/CSU and the SPD agreed on a substantial fiscal package largely dedicated to defense spending and infrastructure. This proposed constitutional reform required a qualified majority of 2/3 in the Bundestag and the Bundesrat to be approved. The sole support of the representatives of the future coalition was not enough to reach this threshold, and the support of the Greens was essential, while the AFD opposes a reform of the debt brake and the radical left party Die Linke does not wish for an increase in defense spending.

The support of the Greens for the project was negotiated in exchange for a commitment to fund decarbonization. The text includes three components:

- The exclusion of defense spending beyond 1% of GDP from the limits of the debt brake. Defense spending is defined broadly at the request of the Greens, who wanted it to include aid to Ukraine, intelligence, cybersecurity, and civil defense.

- The establishment of an off-budget infrastructure fund of €500 billion (11.6% of GDP in 2024) over 10 years. This corresponds to about 1% of GDP in annual spending. The covered areas would include education, transportation, decarbonization, housing, and measures aimed at strengthening economic resilience. €100 billion would be transferred to the climate and transformation fund KTF.

- The authorization of a structural deficit for the Länder of 0.35% of GDP, whereas they were previously required to be balanced.

The project received 513 votes out of 733 in the Bundestag during the vote on March 18 and is set to go to the Bundesrat on March 21.

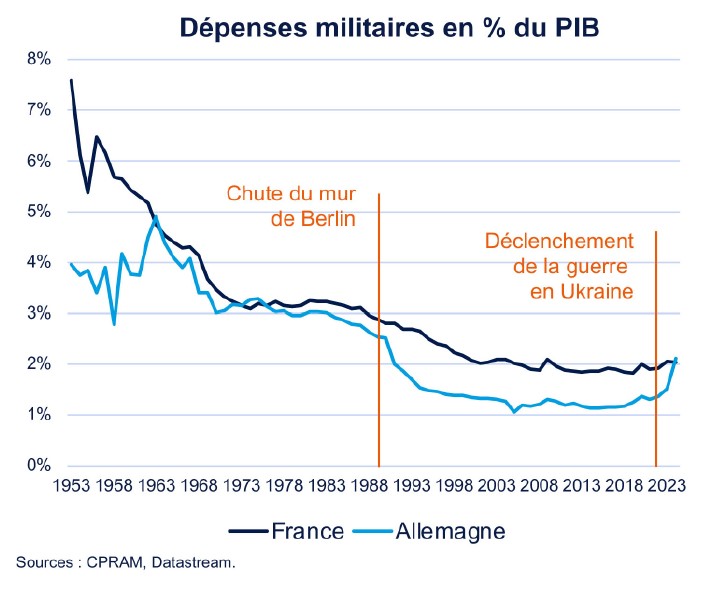

Military spending: an acceleration after decades of underinvestment

Over the past 30 years, German military spending has remained well below the NATO target of 2% of GDP, leading to a cumulative investment deficit of over €600 billion. Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, German military spending has increased considerably, rising from 1.3% of GDP in 2021 to 2.1% of GDP in 2024, or from €48 billion to €92 billion. The objective that appears to be emerging at the European level is to reach 3% of GDP by 2030, which would imply additional annual spending of around €50 billion by that time.

In 2024, the federal budget allocated €53 billion, or 1.25% of GDP, to defense spending. The remaining 2.1% of GDP allocated to defence is covered by an ad hoc fund of €100 billion, which will expire in 2026. If military spending above 1% of GDP were no longer included in the debt brake, this would free up 0.25% of the federal budget (€10 billion) for other expenditures.

A dire need for infrastructure investment

In terms of investment, Germany also stands out for its public spending, which is much lower than the average in the eurozone: 2.5% of GDP on average over the past 15 years, compared to 3.2%, and even lower than the United States, which spends an average of 3.7% of GDP. The prolonged weakness of public investment has pushed Germany to 27th place in the world for infrastructure quality in 2024 in the Global Innovation Index (compared to 12th place in 2020, for example).

The shared responsibility for infrastructure management between the federal government and the Länder, which are subject to severe budgetary constraints, further complicates matters. The announcement of an easing of the Länder's financial constraints and the allocation of part of the infrastructure fund to them are important elements for the plan's success. A boost for growth, but rather in the medium term.

These investments in defense and infrastructure will be very positive for German growth and, consequently, for that of Europe. However, their impact is difficult to assess in the absence of details on the nature and timing of the planned spending. The budget multiplier, i.e., the ratio between public spending and its impact on economic activity, is high for capital expenditures (above 1). For the defense component, the literature provides widely varying conclusions on the level of the multiplier depending on the nature of the expenditures.

Indeed, it will be necessary to determine whether the spending will specifically target personnel, intermediate consumption (ammunition), or equipment investments. It will then be necessary to determine the proportion of spending that will be allocated to local production and that which will be imported. Finally, these expenditures may take a long time to implement and therefore may not have an impact on economic activity in the short term but rather in the medium term (2-3 years).

Significant fiscal capacity

The German announcement is all the more important given that the country has the fiscal room to significantly increase its investments. Indeed, the debt-to-GDP ratio is barely above 60%, much lower than that of other major eurozone countries, and the budget deficit has stabilized at 2% of GDP post-COVID. The proposed plan would increase public spending by around 2% of GDP on average and lead to an increase in debt of €90 billion per year.

The budgetary announcements of the likely new German Chancellor, Friedrich Merz, if implemented, would mark a break with the extremely cautious attitude that prevailed during the Merkel years. Greater German public investment would have far-reaching consequences: increasing potential German growth, supporting long-term European growth, and converging public debt trajectories. It is for all these reasons that the bond market reaction has been so powerful.

The portfolio manager's view

« The budgetary announcements in Europe, and in Germany in particular, are remarkable for their magnitude. This has triggered a sharp rise in German yields: on March 5, the 10-year yield even saw its largest single-session increase since Germany’s reunification. That said, we believe current levels represent attractive entry points into the European bond market, as these budget plans will take time to be implemented and therefore to have an impact on European growth, and because the ECB is expected to continue lowering its key interest rates. With each significant budget plan announcement, the effect is initially very strong and then gradually dissipates. »