From China to India, a demographic relay

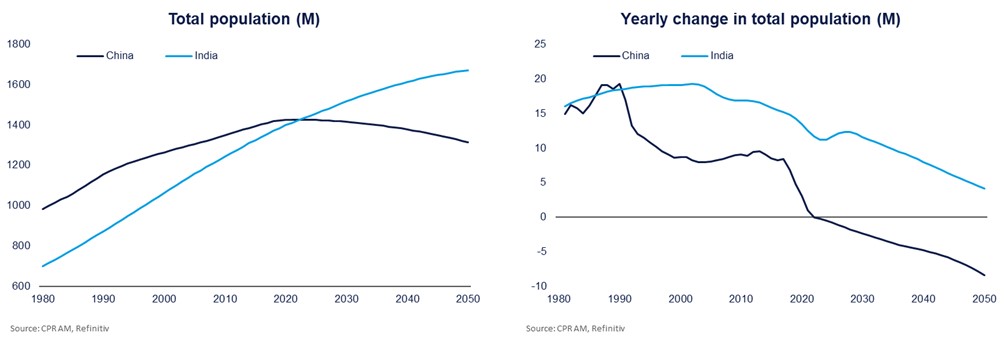

A historic demographic event occurred in 2023: India became the world’s most populous country, a distinction that China had held for several centuries. The two giants’ combined populations is currently 3 billion, or more than one third of the worldwide total. Their demographic dynamics accordingly have a significant impact on the entire planet. Even so, the two countries feature opposing trajectories, and that is what we will detail in this article.

Published on 7 June 2024

The Chinese population is shrinking, and this is only the start…

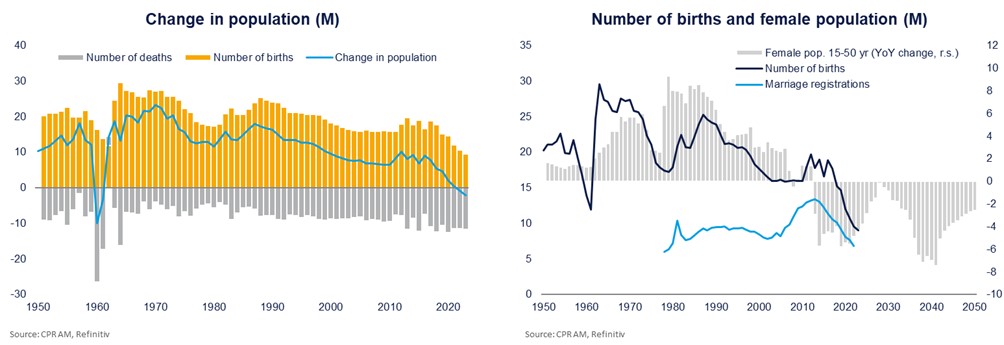

Here’s an alarming figure: the Chinese population declined for the second consecutive year in 2023. After having already fallen by 850,000 in 2022, China’s population shrunk by more than 2 million in 2023. While the number of deaths naturally rises as the population ages, it’s mainly the number of births that is driving this phenomenon.

In 2023, China hit a new low, at just 9 million births, half as many as the last trough before that, in 2016-2017. China’s birthrate per 1000 habitants has fallen faster in recent years and could fall below Japan’s for the first time since 1950.

The recent decline in the birthrate is not a circumstantial phenomenon

Several factors have been put forth to explain this demographic trajectory, but the main one is no doubt the central government’s adoption of a nationwide birth-control policy beginning in the 1970s, bringing to a sudden halt the headlong population boom that followed the great famines.

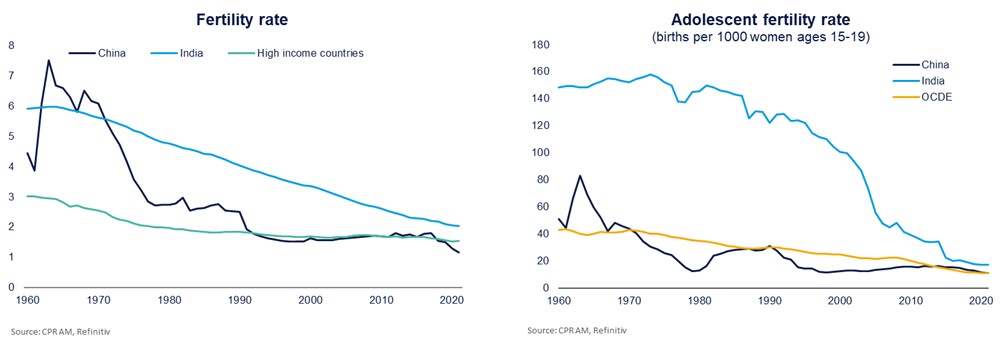

The one-child policy was not officially enforced until 1979, but the birthrate began to decline long before that, from more than six children per woman in 1970 to 2.73 in 1980. The birth-control policy was nonetheless maintained for several decades thereafter, albeit while being eased several times over the years. The maximum number of children per couple increased to two in 2016 and then three in 2022. But easing was not enough to restore China’s natality rate.

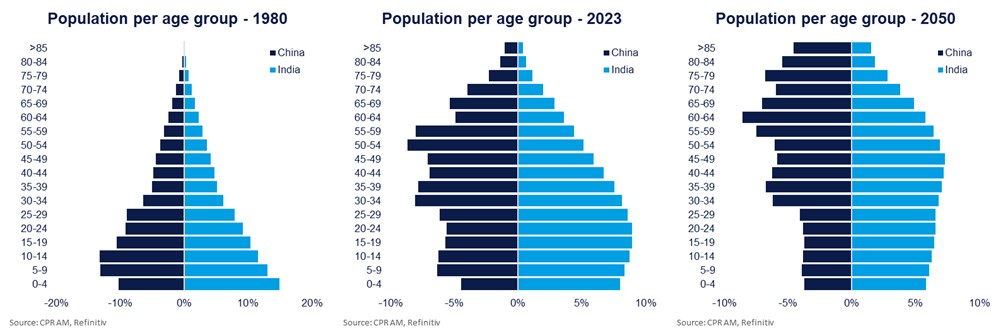

The single-child policy has created major distortions in China’s population breakdown, of which the ratio of men to women is the best known. They will have decades-long repercussions on its population dynamics. Coupled with successive waves of births echoing the baby boom of the 1960s, the dynamics of the Chinese age pyramid is a second explanation for the steep drop in births in recent years. Since 2013, the number of women of child-bearing age has declined at the almost continuous rate of 5 million per year on average, a phenomenon likely to last for several more decades, according to United Nations forecasts.

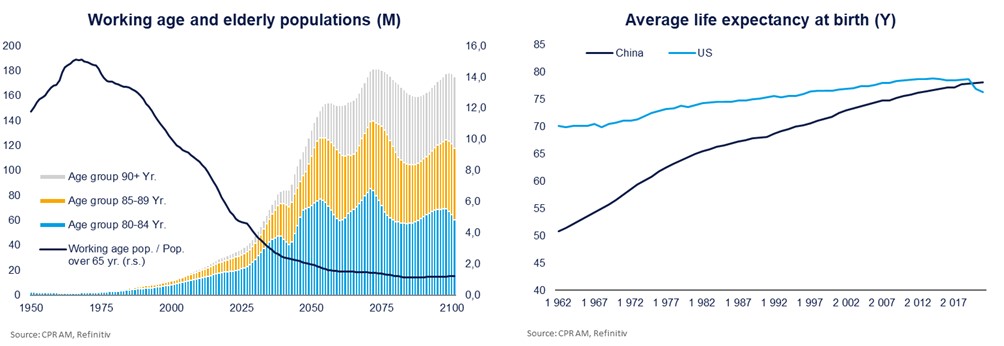

The ageing of the Chinese population will accelerate rapidly

The falling birthrate is the main reason for Chinese demographic imbalances but not the only one. China is also having to deal with an ageing population, a phenomenon that is accelerating. The proportion of persons older than 65 continues to grow and now exceeds 15% of China’s total population. The total number of persons older than 65 has more than doubled within two decades and is expected to exceed 400 million by 2050 (including 150 million older than 80) before receding.

This very rapid rise in the number of seniors is an even greater challenge as their share of the population has already risen very sharply in recent decades. The population of working age was 10 times higher than the population older than 65 in 2000. By 2022, this ratio had fallen to just 5.2 in 2022 and is expected to fall below 2 after 2050. In 2022, the old-age dependency ratio approached 20% of the working population. And while the gap remains wide compared to high-income countries (which have an average ratio of 30%), it has recently narrowed considerably. In addition to the population breakdown, another reason for this is the improved standard of living in China. In 2020, China’s average life expectancy upon birth exceeded that of the US for the first time in recent history.

When combined with declining birthrates, this speedy ageing of the Chinese population has caused considerable risks for the world’s second-largest economic power. It is making Beijing fully rethink its socio-economic model through this new prism. Productivity gains, pension funding, and the development of a “silver economy” will remain key issues in the coming years. The authorities have laid the foundation of a large-scale plan on this latter point, which is an encouraging sign.

The population of this huge country is beginning to decline, but this is only a start, given the structural decline in the birthrate. Moreover, the trend is likely to accelerate in the coming years, and China’s population is expected to fall by more than 100 million by 2050 in the United Nations median scenario – which explains the focus on productivity gains. The massive increase in the number of seniors in the coming years will force China to overhaul its socio-economic model.

India, a new global demographic engine

Like China, India has experienced very robust population growth since the middle of the 20th century. Its population has doubled since 1980, while expanding by an annual average of 17 million. But while China’s population has already begun to decline, the United Nations forecasts non-stop growth in India’s population until 2065, when it will peak at almost 1.7 billion. In addition to this relay, we will see that the differences between the two Asian giants is not a mere question of timing. While this “demographic dividend” is the main explanation for the economic growth gap expected between India and most other countries, it is not a foregone conclusion.

Major divergences with the Chinese trajectory

India is now the world’s most populous country and a major driver of global population growth, but has little else in common with China. The two country’s demographic profiles remain intrinsically linked to “country” specificities, and India’s anticipated trajectory is significantly different from China’s in several ways.

Reassuringly, India’s demographic trajectory that is far less rocky than China’s. A comparison of their fertility rates over the past few decades is telling. And yet, India also addressed population planning issues as far back as the second half of the 20th century. But unlike China, it implemented policies less rapidly and less coercively (albeit, with millions of forced sterilisations), causing a mere shift in its demographic trajectory and not a sudden break. The raising of the age of marriage and the collapse of the birthrate among teenagers are illustrations of this. Keep in mind, however, that the number of children per woman in India, still over 2, has nonetheless fallen three-fold since the 1960s.

In addition to its trajectory, India’s population structure is very different from China’s. It stands out in particular in its relative youth, with a median age of 28 in 2023, vs 39 in China and 45 in the EU. The gradual nature of India’s demographic transition will allow it to remain a young country for several more decades (particularly in comparison with other major economic powers) and, hence, to maintain a very high population of working age. In fact, the working-age population is expected to exceed 1 billion within three years.

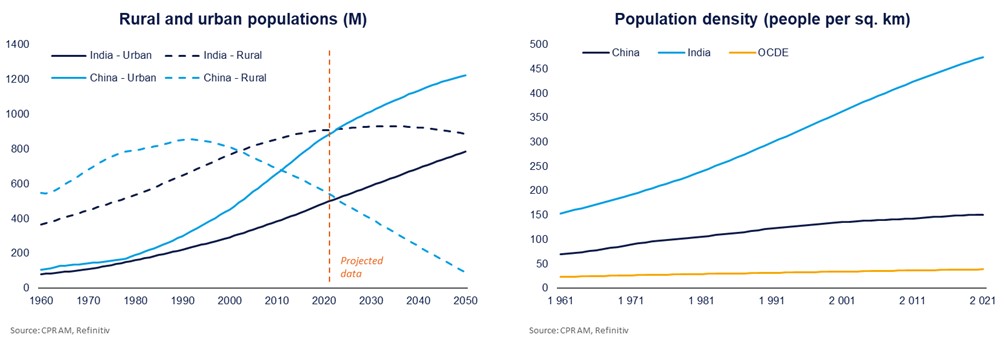

Another meaningful difference is the geographical occupation of territory, particularly the urban-rural breakdown of population. Since the start of the 1990s, the increase in the Chinese population has come with a massive rural exodus. The rate of urbanisation was just 20% in 1980 and 60% in 2020, but will approach 95% in 2050! In the case of India, population growth is one cause of urban growth, but not the only one. The number of people living in rural areas – currently two thirds of India’s population – is thus likely to continue growing until 2035 and then stay close to 900 million. Although also growing fast, the urban population is also likely to remain far into the minority until at least 2050.

There are several reasons for this change. With almost 475 inhabitants per km2, the Indian population is already very dense – three times more so than in China and 12 times more than in the OECD in 2021. The level of economic development is also key, particular the nature of employment. In India, employment is mostly agricultural (43%) and it has far fewer industrial workers than China. The labour market is also still highly fragmented, with more than 250 million free-lance workers. And, lastly, the Indian population remains highly heterogeneous, and the socio-familial structure less favourable to moving about – for women in particular – which is not the case in China and has led to the emergence of commuter town.

India will have to step up efforts to safeguard its demographic capital

Population growth is generally regarded as a decisive factor in potential economic growth. It should therefore be a factor in support of economic growth in India, whereas it’s the opposite in many countries, led by China. But to pay off, this demographic transition must come with suitable public policies.

The World Bank recently sounded the alert on the fact that this store of growth could be underexploited by many countries experiencing strong population growth and that will have to create a considerable number of jobs in coming years. Unemployment is indeed one of the weaknesses of the Indian economy. However, some progress has been made, driven by economic policies focusing on developing the manufacturing and technological sectors and encouraging greater openness abroad. The development of AI is expected to create almost 1 million jobs in India by 2026. An equivalent figure (but over a 15-year period) has also been announced following the agreement entered into with the European Free Trade Association.

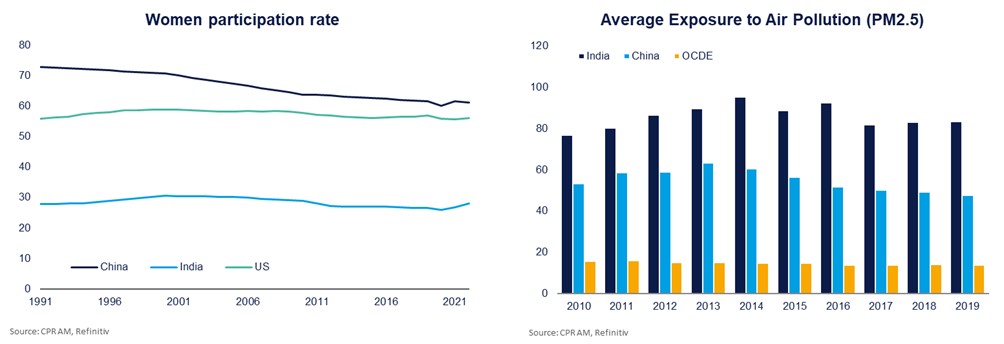

But, well beyond the labour market, population growth must come with substantial public efforts in several areas, if it is to pay off and ensure sustainable economic development. One of the first challenges is education. India’s literacy rate was just 76% in 2022, according to the World Bank, far lower than in developed economies or even China (97%). Urbanisation is expected to increase in coming years and is another factor to take into account in rethinking land-use planning – in connection with climate issues in particular. Managing health issues is another major concern, as they will certainly impact population dynamics. Air pollution is estimated to cause more than 2 million deaths each year in India, and to shorten average lifespans by almost five years (by 12 years in Delhi!).

On top of the health issues, the World Bank estimates that air pollution subtracts 0.6% from Indian GDP each year. And, lastly, the fight against poverty and reducing inequalities in the broadest sense, is also crucial. India’s disparities are particularly flagrant in terms of gender, with a female workforce participation rate among the world’s lowest – in 2022, it was just 28%, or half as high as in the US.

India’s population will continue to rise sharply in the coming years, but its demographic transition will be very different (less chaotic) than China’s. Its demographic momentum and young population will endow it with a substantial demographic dividend. But if India is able to establish itself as a driver of global economic growth, it must first meet many challenges to ensure its long-term sustainable development.

“The other countries experiencing strong demographic growth”

In a 2022 report on the demographic outlook, the United Nations suggested that more than half of world population growth between now and 2050 would occur in just eight countries: the DRC, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines and Tanzania. Africa is by far the continent where the population is expected to expand the most in the coming decades, wqith, according to these projections, 60% of the increase in global population by 2050. It is in the DRC where population growth is expected to be the most spectacular, more than doubling, from 97 to 215 million. Meanwhile, Nigeria is expected to equal the US in population by 2050 (at about 375 million), making them tied for third worldwide in population.