Markets and strategies

Tech : A new bubble or a new cycle?

Tech companies have delivered impressive stock performances recently, so much so that some observers say a tech bubble is taking shape. We offer an update on the topic in this article and wonder whether a new tech cycle might be on the cards.

Published on 23 April 2024

Head of Research and Strategy, CPRAM

Deputy Head of Global Thematic Equities - CPRAM

Tech stocks : a stock run in three stages since 2020

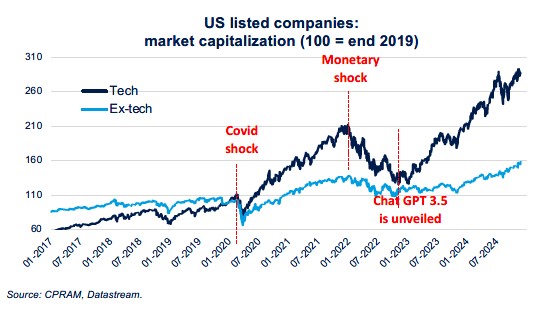

US tech stocks have skyrocketed by 187% since the end of 2019, whereas US non-tech stocks have gained just 59%. This remarkable outperformance has not, however, been a linear one and we can actually distinguish three separate phases during this period:

The Covid shock (2020/2021)

During which the equity markets as a whole lost ground in the first few months of 2020, followed by some particularly spectacular performances from the technology sector up until the end of 2021.

The tech industry was able to outperform during this phase thanks to powerful monetary easing by the Fed (which tends to favour growth stocks, all else being equal) and to the surge in digitalisation triggered by the Covid pandemic (as remote working became much more widespread).

The monetary shock (2022)

Tech stocks peaked during the last few days of 2021. Then, at the very start of 2022, it became increasingly clear that the Fed was going to raise its interest rates in order to tackle high inflation. Bond yields jumped as a result, and growth stocks were hit much harder than others. The technology sector turned in steeply negative performances throughout 2022.

The Artificial Intelligence shock (2023 - ?)

The launch of Chat GPT 3.5 opened up new prospects for the potential and use of Artificial Intelligence, kicking off a cycle of large-scale corporate investment in AI technology. Tech stocks therefore trended sharply upwards again, mostly driven by the Magnificent Seven. The prospect of a Fed pivot (i.e. the Fed reversing course from monetary tightening to monetary easing) has provided tech stocks with further impetus since late 2023.

Tech bubble or not ?

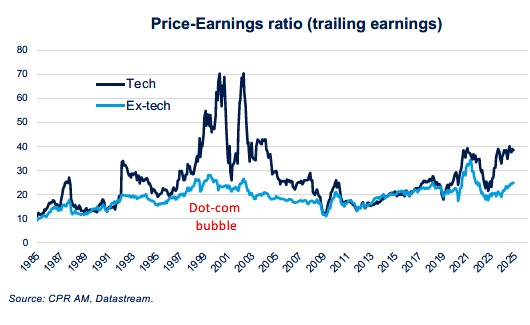

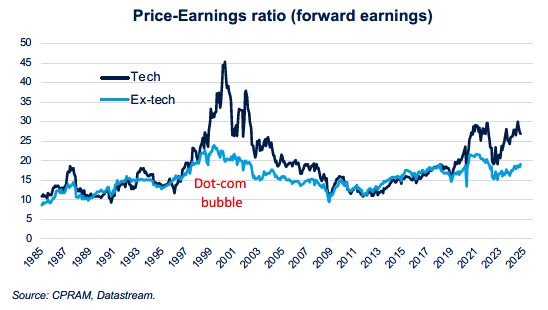

Impressive stock performances from the technology industry in recent years have, of course, raised questions about the possibility of a bubble forming in the sector. Some observers have talked about a repeat of the dot-com bubble that occurred in the late 1990s. The traditional approach to valuing a given equity market or sector is to compare stock-market valuations with (12-month trailing or 12-month forward) corporate earnings, i.e. to calculate PE (price to earnings) ratios.

If we carry out this exercise over a relatively long period, we can see that the technology sector’s PE ratio used to trend in line with that of non-tech sectors but then began to diverge in 2020, since when the technology industry’s PE ratio has risen much faster than that of non-tech industries. We can also see that the PE ratios reached by the technology sector recently are well below (about half) those observed during the dot-com bubble: the first conclusion we can draw from this is that the unwarranted optimism prevailing in the late 1990s does not at all apply to the same extent today. The euphoria surrounding technology companies at the time arose despite the fact that they were generating little profit and their earnings growth was not all that strong.

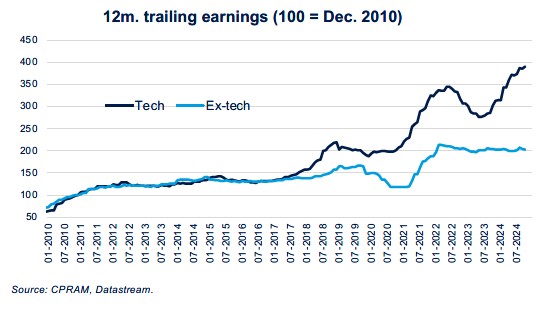

The backdrop today is a completely different one as technology companies are churning out extremely fast earnings growth.

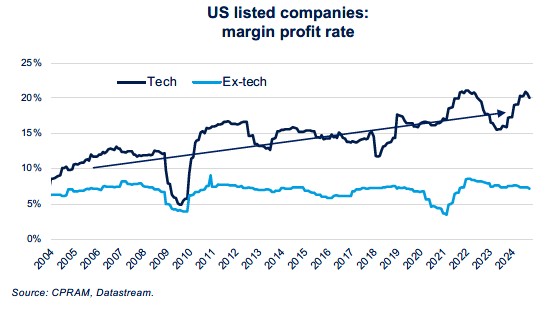

Tech firm earnings are currently trending very positively indeed. First of all, their margin rates have risen for the past 20 years, which has by no means been the case for the rest of the US stock market. Secondly, a close analysis of the earnings momentum generated by US listed firms in the past 15 years shows that tech company earnings trended in line with the rest of the market between 2010 and 2017 but then embarked upon a much more virtuous cycle from 2018 onwards. Tech earnings have actually grown 2 to 3 times faster than non-tech earnings since the end of 2017.

Admittedly, the path has not been a linear one, but the overall trend is very positive and far stronger than for non-tech companies, which appear to have been penalised by the sluggish US economy in 2022/2023.

The markets are still traumatised by the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, which means that fears of a new bubble arise whenever the technology sector enjoys a period of outperformance.

This is what happened in 2013/2014, for example, when the Nasdaq outperformed the S&P 500 by a wide margin: this triggered a whole series of articles in the press wondering whether a new tech bubble was taking shape. But the Nasdaq did not underperform in the years that followed.

The same question arose in 2018/2019: one CNBC article from March 2018, for instance, argued that “Tech stocks are flashing a warning sign similar to before the dot-com bubble popped”, and the headline of an International Banker article from October 2019 asked “Is a bubble forming in tech stocks?”. And yet the only year in which the US tech sector has underperformed within the past 10 years was 2022; this was the year that saw the most aggressive monetary tightening by the Fed since the early 1980s, which naturally hit fast-growing companies harder.

It is worth pointing out here that the 2024/2025 phase differs from 2022 as the world’s main central banks are currently in the process of reverting back to a cycle of interest rate cuts, which should prove to be relatively more favourable for the technology sector. Setting this positive argument aside, the real question to ask is whether the sector is embarking upon a new tech cycle.

A new cycle of tech stocks?

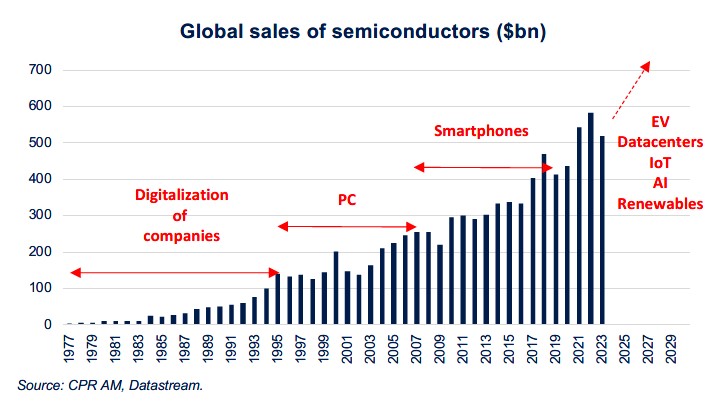

Moore’s Law, formulated in 1965, posited that computing power grows exponentially, with the number of transistors per electronic chip doubling every two years. This empirical relationship has indeed held so far, slashing computing costs from one decade to the next. This has allowed a new technology cycle to take shape every 15 years on average: from the mainframes of the 1960s to the mini-computers of the 1970s, giving way to PCs and smartphones in more recent decades. Demand for semiconductors has tripled or even quadrupled with each cycle.

This demand is now getting a boost from emerging megatrends such as the Internet of Things (IoT), renewable energies, electric vehicles and artificial intelligence (AI), all of which are triggering another major tech cycle. Algorithms (sequences of instructions used to resolve very specific problems) play a crucial role in the added value creation that is driving widespread adoption of these new themes. The mechanisms in question are referred to as being ‘silicon dependent’, i.e. they tap into technological progress in the field of semiconductors (e.g. the ability to process ever increasing amounts of data), for which demand is thus picking up again.

Datacentre architecture is being disrupted by the emergence of conversational AI, which is itself a product of LLM (“Large Language Model”) maturity. Parallel processing, a method that uses Graphics Processing Units (GPU), is emerging as a new paradigm, emphasising the crucial importance of combining computing power with network speed and storage to create a “super brain”. The market for AI datacentres could be worth $400 bn by 2027 (versus $52 bn in 20231). Such growth would have ripple effects on the rest of the technology industry, as it would create critical infrastructure not only to develop new products but also to step up the customisation and quality of these products while offering additional productivity gains.

So, it is clear that we are at the dawn of a new cycle of innovation and disruption, with emerging technologies set to continue overhauling the industrial and economic landscape for the next 15 years. Not all the effects of this new technology cycle are going to be perceptible straight away, and it is too soon to predict all the long-term repercussions with any degree of certainty. New industries emerged from the dot-com stock euphoria of the 2000s, and they have redefined the global economic landscape: social media and e-commerce have given rise to industrial behemoths, and we have witnessed the emergence of new technological platforms and ecosystems. Similarly, the new technology cycle now taking shape will prove to be a game-changer for the stock markets.

Conclusion

Tech stocks have delivered impressive stock performances recently in comparison with the rest of the market since 2020, so much so that some market observers wonder whether a bubble is forming along the lines of that experienced in the late 1990s.

However, the situation today differs from that of the dot-com bubble in a major way: the euphoria surrounding technology companies at the time arose despite the fact that they were generating little profit and their earnings growth was not all that strong, whereas tech firms today are delivering extremely rapid earnings growth. So the unwarranted optimism of the late 1990s in no way applies to the same degree today.

What does appear to be taking shape is a new technology cycle, with progress being made in the field of semiconductors and certain artificial intelligence technologies reaching maturity.

We therefore feel optimistic about the technology industry’s medium and long-term outlook, even if it is obvious that performances will not be linear and that all technology stocks will not evolve in an undifferentiated manner: as in any new cycle, winners will emerge and companies will be disrupted.