US presidential election: "Climate on the line"

Kamala Harris and Donald Trump have opposing views on many topics but this is particularly the case as far as climate is concerned.

Published on 17 October 2024

In this piece, we will discuss what part climate challenges will play in the 2024 US presidential elections, while pointing out the climate convictions of the Republicans and Democrats, and the role of executive orders in climate policy, in US commitments to the Paris Agreement, and in risks to the Inflation Reduction Act.

On the reality of climate change

- For Kamala Harris, climate change is an “existential threat” and it is urgent to act to counter it. On the whole, the Democratic party is closely aligned with combatting climate change. Kamala Harris has not tried to use climate change as a campaign theme but a possible Harris administration would probably be an extension of the Biden administration.

- In December 2023, Donald Trump said that there was no point in “worrying about global warming” and he has often downplayed its consequences.

- During a Republican presidential primary debate, candidates were asked the following: “Raise your hand if you believe human behaviour is causing climate change.” None of them did so. That doesn’t mean that no one is the Republican party is worried by climate challenges, given that a group of 81 Republican members of the House of Representatives founded the Conservative Climate Caucus (acknowledging that human activities contribute to climate change is a requirement to join).

The role played by executive orders in climate policy

The US Constitution grants the president broad discretionary power through executive orders, which have the force of law. However, the president cannot unilaterally commit to new spending or new fiscal receipts, as it is Congress that has the “power of the purse”. In the case of climate and environment, the president can unilaterally change regulations but cannot alone decide on public investments or green tax policy.

While president, Donald Trump used executive orders to cancel or ease more than 100 environmental regulations (for example, cancelling the requirement that oil & gas companies report their methane emissions and authorising drilling in previously protected zones). A number of these decisions were reversed by Joe Biden through executive orders after he became president.

During his term of office, Biden has issued one executive order setting a target of 50% electric vehicles nationwide and another requiring that all federal administration vehicles be EVs by 2027. Yet another executive order stipulates that all electricity used by federal agencies be generated by clean energies by 2030. And, in January 2024, Biden paused government permits of infrastructures used in exporting LNG.

So executive orders will play a major role in climate policy from 2025 on. If Trump wins the 2024 presidential election, a new wave of deregulation via executive orders, and very likely, permits for many new oil & gas projects can be expected (one of his campaign slogans is “Drill, baby, drill.”) On this point, Kamala Harris has backtracked on her proposal made a few years ago to ban fracking.

That said, executive orders can’t do everything. Biden could not have passed the Inflation Reduction Act in summer 2022, which mobilises major financial resources, without the participation of the House of Representatives and Senate, both of which were majority-held by the Democrats. And the Democrats’ very slim majority at that time in the Senate (with just 50 seats out of 100) had forced Biden, under pressure from Joe Manchin, to sharply curtail the IRA. Bottom line: we can see that US climate and environmental law will depend not just on who wins the presidential election but also the elections to the Senate and House of Representatives and these Congress elections look very tight as well.

The US and the Paris Agreement: in, out, back in…

In 2015, 196 countries signed the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty whose objective is to keep “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels”.

The United States was one of those countries. President Barack Obama signed the agreement on 29 August 2016 via an executive order, allowing him to bypass a Republican-controlled Senate. However, it was also through an executive order that Trump exited the agreement on 1 June 2017. Biden then signed an executive order to rejoin the agreement on the first day of his presidency, on 20 January 2020. The split between Biden and Trump on climate change is quite stark here. It is quite possible that a new Trump administration will mean a second exit from the Paris Agreement.

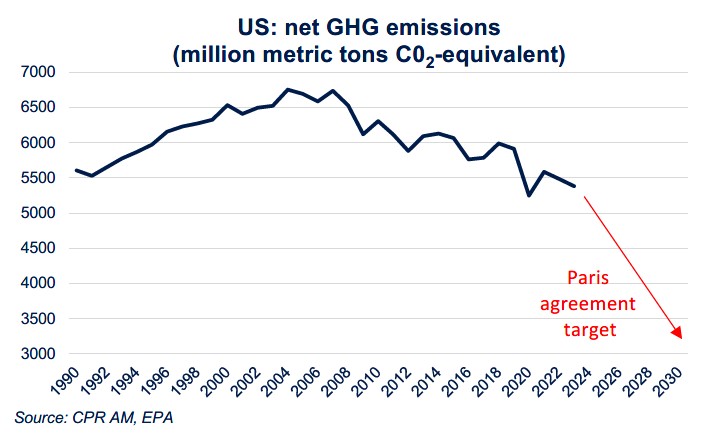

In accordance with the Paris Agreement, the Biden administration in 2021 submitted a “nationally defined contribution” setting an objective of net greenhouse gas emissions reduction at 50% to 52% by 2030 vs 2005 levels. The Rhodium Group estimates that net greenhouse gas emissions in 2023 were about 17% below 2005 levels. So, the US will have to decarbonise its economy faster if it intends to meet its Paris Agreement commitments.

Is the Inflation Reduction Act at risk?

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was passed in summer 2022 through a budget reconciliation process (as a way to bypass the filibuster rule) and was described by the Biden administration as “the most ambitious investment in combating the climate crisis in world history”. In the Senate vote, it was Vice President Kamala Harris who broke the tie, with 50 Democrats voting in favor and 50 Republicans voting against.

Among other things, the IRA included tax credits for households when buying an electric vehicle, a heat pump or solar panels. It also included clean-energy tax credits for private-sector companies, including the rollover until the end of 2024 of tax credits for producing and investing in renewable energies (wind and solar power, biomass, as well as hydropower), the rollover until 2033 of tax credits for carbon sequestration, a tax credit for green hydrogen production and a tax credit for nuclear power generation. The IRA’s cost was initially put at $369bn over 10 years, but could be much higher if demand is there, as the number of tax credits is not capped.

One year after its adoption, in August 2023, the Biden administration estimated that the IRA has already created more than 170,000 jobs in clean energies (it projects 1.5 million over the next 10 years) and that the private sector has already announced more than $110bn in investments in clean technologies, including more than $70bn for EVs.

One fear of many stakeholders is that a Republican victory in 2024 will mean a dismantling in the IRA. And it’s true that Trump recently criticised some IRA portions, particularly those for EVs and wind power. But things are not so simple, for at least three reasons:

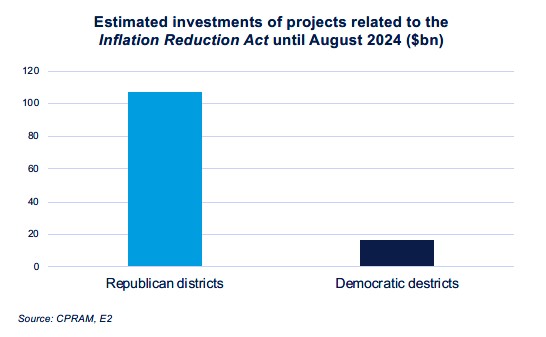

- The IRA has benefited many Republican districts. An NGO (E2) has found that almost three quarters of jobs created in the first two years of the IRA were in Republican districts.

- A Republican president will not be able to cancel the IRA without a majority in both houses (it’s Congress that has the “power of the purse”). However, the president would be empowered to toughen or ease some IRA provisions, if he so wished.

- A Republican president with majorities in both houses would not necessarily be aligned with those majorities. We mentioned above that more than one third of current Republican congresspeople are members of the Conservative Climate Caucus, and as a group they would not necessarily be naturally inclined to reverse a law intended to combat climate change. In the event of a Republican “trifecta” (i.e., the presidency and majorities in both houses), mechanisms covering EVs and renewable energies would be the most at risk. But, here again, major EV and renewable energy projects have been launched in some Republican districts, and the congressmen or senators concerned would probably be hard-pressed to make decisions that would jeopardise them.

In contrast, in the event of a Democrat “trifecta”, it is quite possible that the IRA would be expanded significantly. After all, the Democrats’ proposals before the IRA was ultimately enacted were far more ambitious.