An ageing population

It is often said that the ageing of the population will be one of the major issues of tomorrow. That is certainly true. But the ageing of the population is also already a major issue of yesterday. This can be seen in a large number of indicators, including the increase of the median and average age, the falling percentage of young people in the total population, the rising percentage of the oldest persons, etc.

Published on 10 June 2024

Let’s take the median age, i.e., the demarcation point at which half of the population is younger and half is older. Globally, the median age rose from about 20 in 1970 to 30 in 2020. The median age has risen on all continents during this period, with the notable exception of Africa, where it has stayed at 18. In Europe, the median age rose from 30 in 1960 to a little more than 42 in 2020. Among the major economies, Japan is one of those in which ageing is the furthest along (with a median age of 48 in 2021), and China is already “older” than the US.

The ageing of the population has resulted from two phenomena: falling birthrates (hence, fewer young people) and longer lifespans (hence, more elderly persons):

- Since the Second World War, women have had fewer and fewer children, from five per woman worldwide on average in 1960 to 2.3 in 2021. There are several reasons for falling fertility rates, such as women’s greater educational opportunities, the steep decline in infant mortality during the period, and access to contraception. In some countries, we are even seeing a collapse in the number of births. In South Korea, for example, the number of children per woman even fell below 1 in the late 2010s (and to 0.72 in 2023).

- Life expectancy rose steeply throughout the 20th century. Let’s take the example of France: whereas life expectancy was 45 for people born in 1900, it was 66 for those born in 1950 and almost 83 for those born in 2021. People over 100, for example, are now far less rare than they used to be.

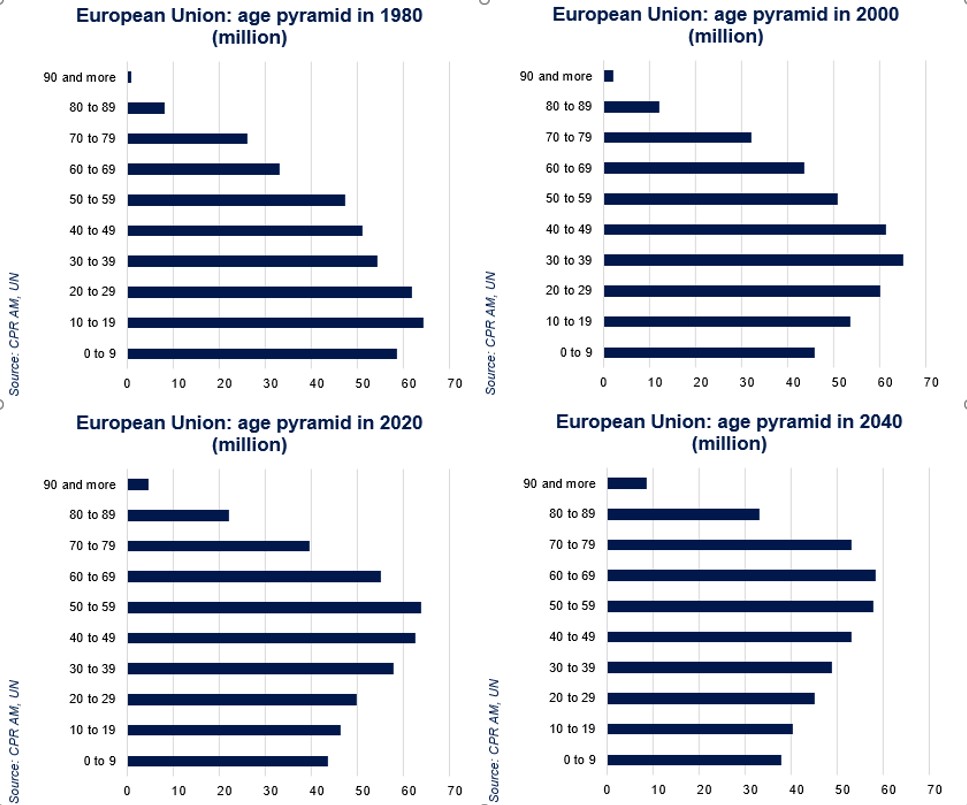

This dual phenomenon of longer lifespans and a lower numbers of births in rich countries and China has skewed the age pyramid. This is especially impressive in Europe, with the advent of the baby boom wave (i.e., the spike in births between 1946 and 1964), which turned 60 in the late 2000s. Whereas in 1980 there were 123 million persons in the European Union younger than 20 and 53 million persons “65 and older”. The two age groups were almost equal in number in 2020 (at about 90 million persons each). According to United Nations projections, by 2050, almost 27% of the population will be older than 65 in Europe and North America.

What will the economic impact be?

The fact that the population is ageing in rich countries and in China has significant economic repercussions, as younger people, people of working age, and older people all have a different relationship with consumption, investment and savings. Most economic and social systems have been built under the assumption that the past breakdown by age group would last forever. But that’s clearly not the case and could lead to a number of imbalances.

Greater and greater pressure on public finances

Let’s first take the ratio of persons of working age (15-64 years) to persons older than 65 (called the old-age dependency ratio). It has collapsed in rich countries in recent decades. In the European Union, it fell from 7.7 in 1950 to 3 in 2021 and is likely to converge to 1.8 in 2050 (according to the United Nations’ median projection). The number of working persons per retiree has therefore declined sharply, and this will exert increasing pressure on pay-as-you-go pension systems (in which the dues paid by working persons are used to pay retirement pensions). In countries where dues are no longer enough to pay retirement pensions, the government can pay the shortfall. This will exert a heavy burden on public finances . Moreover, healthcare spending will automatically rise with the increase in the number of elderly persons. (Incidentally, one of the challenges of the ageing of the population will be to find enough caregivers. An initial alert was sounded after the Covid crisis with labour shortages at hospitals, for example). Broadly speaking, the ageing of the population will place a heavy burden on public finances. An OECD working paper released in late 2022 found that public healthcare spending, long-term healthcare, and public retirement funds would rise by 5 percentage points of GDP between 2021 and 2060 in OECD countries (based on a median projection), with wide disparities between countries.

An impact on interest rates via shifts in savings

The ageing of the population also has repercussions on savings. According to the lifecycle theory developed by the Nobel Prize laureate Franco Modigliani , young workers take on debt (to buy a home for example), older workers save for their retirement, and retirees dip into their savings by liquidating their assets afterward. As a result, the fact that a larger portion of a given country’s population saves for retirement (typically between the ages of 45 and 64) should increase aggregate savings, which would mean downward pressure on interest rates. Empirical research has generally concluded that the ageing of the population has pushed interest rates down in recent decades3. On the contrary, the fact that a large cohort of the population is older than 65 and is dipping into its savings is supposed to push interest rates up. The exact timing is especially hard to estimate, as it is possible that savings behaviours will not fall in with theoretical predictions. Keep in mind, moreover that a large number of factors can influence interest rates, including supply-chain issues, energy crises, etc.

A disrupted job market

With longer lifespans, debates on how to organise work are becoming increasingly recurrent, regarding retirement ages, the sharing of working time, training opportunities or changing jobs during one’s career. These issues are especially hard to deal with, given the range of situations: whereas persons having held intellectual professions may wish to work longer, such is not necessarily the case of persons having held physical or harsh jobs. Another thing to keep in mind is that increased life expectancy does not always mean an increase in “healthy life expectancy”. The skewing of the age pyramid reflects a shrinking population of working age in a number of countries (in Europe, as well as Japan and China), which may cause labour shortages.

Are demographic phenomena now inflationary?

One of the major issues regarding ageing of the population is whether or not it will be inflationary. On this point it may be tempting to extrapolate what happened in Japan, the country the furthest along in the phenomenon of ageing and that has experienced excessively low inflation over the past three decades. However, Japan is a very special case for two reasons: 1) the bursting of the financial bubble of the 1980s, which unfolded over at least two decades and undermined the balance sheets of private companies and economic activity in general; and 2) the fact that the female workforce participation rate rose faster than in other developed countries (albeit from a lower base), thus triggering a supply-side shock on the labour market, which by nature is deflationary. So, population is probably not the factor that had the greatest impact on inflation in Japan.

In reality, the ageing of the population is likely to contribute to structurally higher inflation in the future. This is the theory presented by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan in The Great Demographic Reversal, a book that has stirred up much discussion among central bankers. There is no economic theory explicitly formalising a link between population and inflation. However, a comprehensive empirical study was done on the links between the age pyramid and inflation by Mikael Juselius of the Bank of Finland and Elod Takats of the Bank for International Settlements4. The two researchers studied 22 countries over a very long period (1870-2016), in which each of those countries experienced their own demographic cycles. This study stood out from previous studies, which focused only on the post-war period. For each country, the researchers laid out the percentage of total population of 17 age groups: 0-4, 5-9, 10-14, …75-79 and 80+ years. The authors then looked at the inflationary impact of the breakdown in population by age group while controlling a number of economic variables, such as real interest rates, monetary aggregates, public debt, or deviation of GDP from its potential. Their main finding was that, all other things being equal, an increase in the dependent population (i.e., persons too young or too old to work) is associated with higher inflation, whereas an increase in the population of working age is associated with lower inflation. However, the authors pointed out that the percentage of persons 80 and older in total population has a very negative impact on inflation. Based on their findings and the expected shift in the age pyramid, Juselius and Takats suggest that population changes will push inflation upward from 2010 to 2050 in all developed countries, whereas they pushed it downward from 1980 to 2010. Indeed, the percentage of persons between 60 and 80 in the total population will increase steeply, which should tend to push up inflation. This is expected to happen in both the US and Europe.

- FMI, 2019, “Macroeconomics of aging and policy implications”.

- Modigliani F., 1966, “The Life Cycle Hypothesis of Saving, the Demand for Wealth and the Supply of Capital”, Social Research.

- BCE, 2019, « Demographics and the natural real interest rate: historical and projected paths for the euro area”, ECB working paper N°2258.

- Juselius M. et E. Takats, 2021, « Inflation and demography though time », Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, vol. 128.