The new silk road: what is the foreseeable impact on agricultural and food products?

The new Silk Road, also known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), is based on a strategy implemented by the Chinese authorities at the behest of Xi Jinping concerning land-based, sea-based, aerial and digital networks. Observers are wondering about a specific potential component of their role in relation to the agricultural and food economy. Is this simply a necessity for the world’s most populous country, or is it part of a strategy to strengthen China’s grip on the global agri-food economy?

Published on 16 October 2022

In particular, this system involves land- and sea-based infrastructure designed to smooth out and speed up the circulation of goods, people and services along the routes in question: ports, road and rail interchanges, and energy, industrial and digital resources. Launched in 2013 by Xi Jinping himself, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) covers not only the whole of the Eurasian continent but also East Africa, where China already has a particularly strong presence.

This strategy has been particularly well received in small countries, where the impact on wealth creation and demographics is clearly visible. In reality, these countries are strategically located along routes defined in the BRI, and the Chinese authorities are making sure financial co-operation remains mostly under Chinese control. Furthermore, some countries, notably in Africa, have seen worrying increases in their debts with Chinese banks.

Cutting transit times and costs

The new Silk Road is, of course, intended to facilitate the transport of all kinds of goods to and from China. Shortening transit times enables transport costs to be cut. Goods are now regularly shipped by train between Eastern China and Europe in under three weeks, compared with more than twice as long by sea.

Land routes, particularly in the case of rail, provide for the development of a halfway house between sea transport, which offers high capacity and is cheap but slow, and air transport, which is fast but expensive.

China increasingly needs commodities

This multi-component strategy is clearly also aimed at agricultural and agri-food products. In the space of forty years, China’s needs have grown to the point where they now far exceed its production capacity. The population has doubled since the early 1960s. Galloping industrialisation in the global factory that is today’s China has brought about a huge population exodus from rural areas to China’s new megacities. The country’s economic development has given birth to a middle class with higher purchasing power and stronger demand for an increasingly wide array of consumer goods.

It thus follows that China increasingly needs commodities, including in particular agricultural commodities. With utilised agricultural area (UAA) accounting for 15% of its total surface area, China has to feed 22% of the global population. Although it has substantially ramped up its production of cereal, cotton, oilseed, sugar, meat and fruit over the past fifty years, it is still not considered self-sufficient. It exports little and its imports remain relatively limited, suggesting that the Chinese authorities are keen to keep control of import volumes irrespective of the population’s actual needs, even at the risk of potential shortages.

China will have to look farther afield for some of its food resources for a long time to come

Just as it continues to depend on imports for a substantial proportion of its energy needs (oil and gas), China is never going to be able to be self-sufficient in foodstuffs. The Chinese authorities’ response is simple: for food consumed directly by humans (cereal, fruit and vegetables, and sugar), maintain self-sufficiency as far as possible; for animal feed, do not pursue self-sufficiency at any cost. This explains the country’s huge imports of cereal – wheat, maize, rapeseed and soya – both directly and in the form of meal.

Under the BRI, food products must play a part not only in reinforcing China’s food security but also in establishing China’s presence and influence with other countries. Paradoxically, however, China could become an exporter, particularly of value-added products. For example, take flax and wood. France alone accounts for over 70% of global flax production, but much of the material ends up in China, which produces 80% of linen textiles; and, while China has long imported industrial roundwood for its own consumption, it has for over 15 years been one of the leading exporters of panels and intermediate components used in furniture-making.

China would like to rebalance transport costs between imports and exports

By developing and speeding up new commercial communication routes through initiatives under the BRI, China would also like to rebalance transport costs between imports and exports. In other words, it is amenable to the smooth running of its new Silk Road being underpinned by an increased role for China as the “factory of the world”.

Through the associated routes and the connections it is promoting and financing, China appears to be open to any and all tactics enabling it to meet domestic demand, gain a foothold in new food markets and, finally, build up a store of currencies by betting on added value.

China could eventually become an exporter of processed food products, no doubt initially to emerging countries in Africa and Central Asia, based on commodities it will never be able to produce entirely on its own, but which will offer it new opportunities to create value.

==> A short history lesson

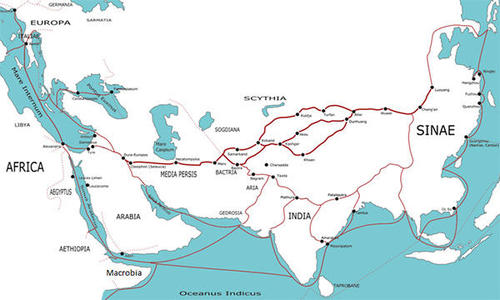

The Silk Road arose from a diplomatic mission sent by Chinese emperor Wudi, of the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), to the Yuezhi kingdom in Bactria (a region located between the modern-day states of Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) to set up a strategic alliance against a common enemy. The ambassador returned thirteen years later with a wealth of information about the lands through which he had travelled, previously unknown to China. Other diplomatic and trade missions followed, and a network of transcontinental routes gradually developed, extending from China to the Mediterranean and passing through Central Asia and Iran, supplemented by sea routes. The reason these routes took their name from silk is that this precious commodity, the secret of whose manufacture was jealously guarded by China until the fifth century, was used as a trading currency.

— Benoît Bousquet – Direction of Economic Studies Crédit Agricole SA