Global governance to preserve biodiversity

While COP 16 is about to take place in Colombia (21 October-1er November), it is worth looking back at the governance of global biodiversity agreements and how they are being transposed into national strategies. This text will also look at the main advances made at previous biodiversity COPs and the main objectives of COP 16.

Published on 21 October 2024

The organisation of "biodiversity" COPs

The "biodiversity" Conferences of Parties (COPs) are based on an international agreement, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), adopted in 1992 at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro.

The CBD has 196 parties, including the European Union, but not the United States, the only major non-signatory to the convention. This agreement has three main objectives:

— the conservation of the ecosystems and biological diversity,

— the sustainable use of the components of biodiversity,

— the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits derived from the use of genetic resources.

Biodiversity COPs take place every two years and aim to implement the CBD by reviewing progress and defining priorities and work plans for the coming years.

Article 6 of the Convention requires the parties to take national measures to achieve the targets set. These are the National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs), which are the equivalent of the NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions) for the climate, even though the NBSAPs are not mandatory, unlike the NDCs. They are therefore the main instruments for applying the Convention, and 90% of the parties have already defined them.

Two biodiversity COPs were particularly significant:

The Nagoya COP 10 biodiversity conference in 2010

It led to the adoption of the Strategic Plan for Biological Diversity 2011-2020, its philosophy was to "live in harmony with nature" by enhancing, conserving and restoring biodiversity.

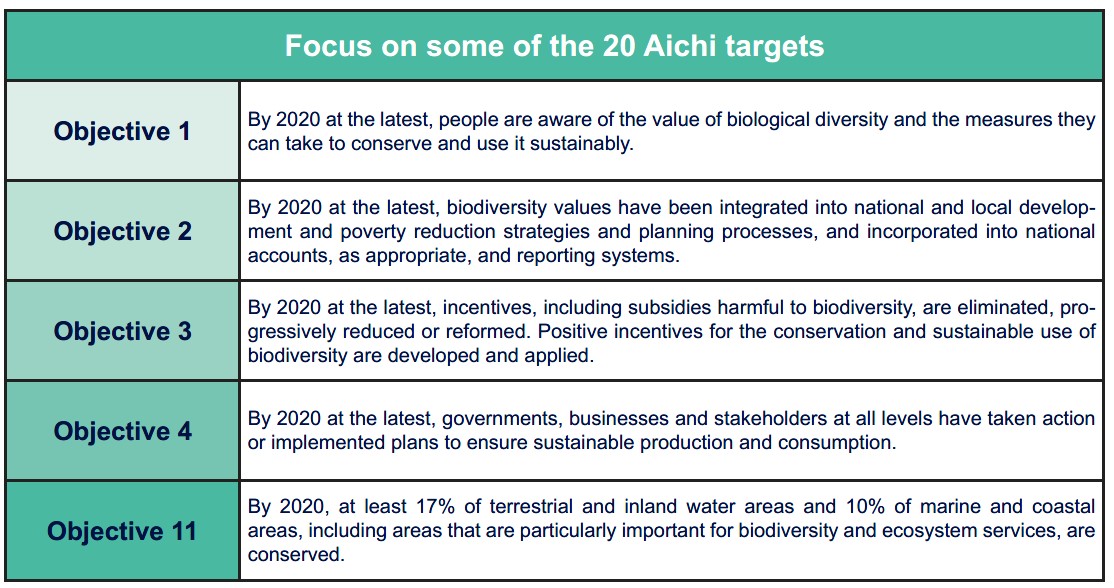

The plan included 20 objectives, known as the "Aichi targets", including taking account of biological diversity in public policies and conserving at least 17% of terrestrial and inland water areas and 10% of marine and coastal areas by 2020. While the need to raise financial resources for the effective implementation of the 2011-2020 Strategic Plan is one of the Aichi objectives, it was not quantified.

Countries were asked to transpose the Aichi objectives into their national strategies by 2015. However, most of them did not do so until 2016, which explains why most of the Aichi objectives were only partially achieved or not achieved at all.

The Kunming-Montreal COP 15 in 2022

COP 15 worked on the basis of the "Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services" published by the IPBES1 in 2019, which is the biodiversity equivalent of the IPCC's climate reports. In particular, it assessed the progress made on the 20 Aichi targets set in 2010: for 4 of them, satisfactory progress has been made; for 7, progress has been made on certain components; and for 6, progress has been deemed insufficient for all components. Finally, for 3 objectives, the lack of data made it impossible to measure the progress of the actions implemented. In addition, the report estimates that of the 16 indicators used to assess the state of nature, 12 have shown continued deterioration over the decade.

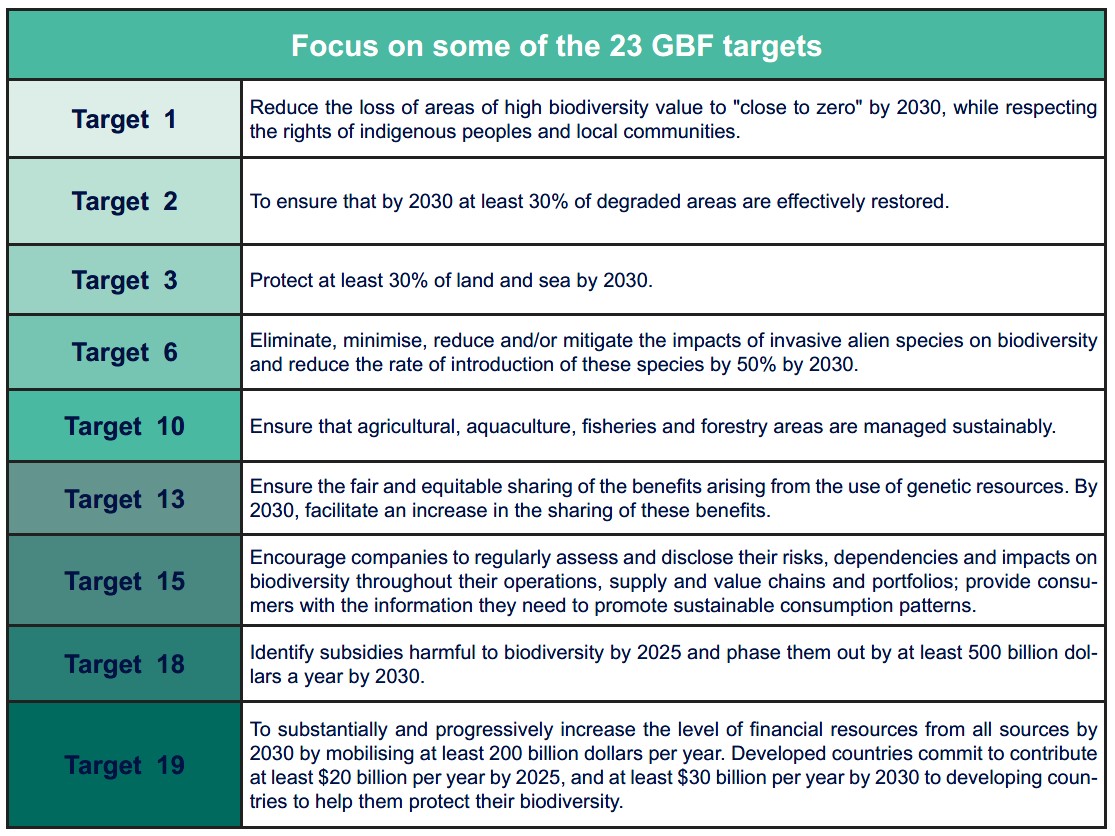

COP 15 set the objectives for the 2020-2030 decade by adopting the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) for the post-2020 period, and has therefore been described as a historic COP and the biodiversity counterpart to COP 21 on climate.

Its main objective is the “30x30 target”, to protect at least 30% of the planet's land, freshwater and oceans by 2030. By 2024, 17.5% of land and 8.5% of marine areas will be protected.

This COP was also marked by its targets for financial commitments: to raise $200 billion a year to protect biodiversity, to help developing countries to the tune of $25 billion a year by 2025 and $30 billion a year by 2030, and finally to reduce subsidies harmful to biodiversity by $500 billion a year.

A study2 by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) in December 2023 estimated that financial flows harmful to nature encountered for almost $7,000 billion a year, including $5,000 billion from private agents and $1,700 billion from public subsidie.

How have the COP 15 commitments been transposed to?

The COP15 agreement stipulated that Parties should submit revised NBSAPs aligned with the 2030 objectives and targets of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework by COP16 or, in the absence of complete NBSAPs, define national objectives as a minimum. It recommended that NBSAPs be drawn up with the participation of all governmental and social stakeholders.

Since COP 15, only 203 of the 196 signatories have submitted national biodiversity strategies and action plans for 2030. Among them, seven European countries (Austria, Italy, Ireland, France, Luxembourg, Hungary and Spain) and the European Union, as a member and signatory of the biodiversity COPs, have published theirs. China, Canada and Japan have also done so. In addition, 47 countries have published national targets in the absence of a NBSAP.

What are the main measures included in the most recent NBSAPs?

- Europe: The Biodiversity 2030 Strategy for Europe was initiated in 2020 and proposed measures that the European Union wished to support at the Kunming- Montreal COP. It was completed and officially submitted to the Convention on Biological Diversity in November 2023.

Several of the measures mentioned have been adopted as part of the Green Deal, including those relating to protected areas, nature restoration, climate mitigation and adaptation, and sustainable agriculture. The EU, along with Ireland and Luxembourg, aims to halt and then reverse the loss of pollinators.

However, certain measures, such as those relating to the use of pesticides, have only been partially adopted at European level, as the regulations on pesticides (REACH) and the Farm to Fork strategy have met with strong resistance from manufacturers and farmers.

- Japan: Japan submitted its national biodiversity strategy in July 2023. In its roadmap for achieving the 30x30 target, Japan aims to gradually increase the surface area and number of protected areas and improve their management. In 2021, 20.5% of land and 13.3% of sea areas were protected.

By the end of March 2023, more than 400 entities - including associations, local governments and businesses - had made voluntary commitments to help achieve this target.

Among the country's main commitments, the strategy for sustainable food systems calls for a 10% reduction in the use of chemical pesticides and a 20% reduction in the use of chemical fertilisers by 2030, as well as a doubling of the area devoted to organic farming. Japan is also committed to increasing financial support for developing countries and to phasing out or reforming harmful subsidies in a fair manner.

- China: China published its Biodiversity Protection Strategy and Action Plan 2023-2030 in January 2024. In line with the 30/30 target, it intends to protect 30% of its territory, inland waters and maritime areas by 2030. It has defined a Master Plan for major projects to protect and restore important ecosystems (2021- 2035): 30% of degraded ecosystems will be restored.

The surface area of nature reserves will represent around 18% of the land area by 2030 and should exceed 18% by 2035. It provides for a reduction in the use of pesticides, but does not include a quantified target. Development plans, including at local level, will have to incorporate biodiversity conservation objectives by 2030. Businesses will be required to provide data on the impact of their activities on biodiversity, and a business biodiversity impact index will be created.

China intends to create a Biodiversity Fund to support biodiversity conservation in developing countries. Finally, China is, along with Canada, the only country to mention the objective of reversing the loss of biodiversity by 2030 in their NBSAPs.

The unique positioning of the United States

It is the only UN member that has not signed the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). At the time, the US Senate did not want the United States to ratify the treaty on the grounds that it could have generated major financial commitments. As a result, there is no national strategy for biological diversity, and this something that some American scientists regret.

However, the United States has taken part in the COP biodiversity negotiations as an observer and is fairly active on the subject. Since the 1970s, a number of laws have been passed to protect biodiversity. One of the founding pieces of legislation dates from 1973 and aims to protect endangered species (Endangered Species Act (ESA)).

Since then, many of the COP commitments have been incorporated into sectoral strategies:

— In 2021, the United States pledged to protect 30% of its land and water by 2030 by releasing $1 billion in funding via a public-private partnership (America the Beautiful).

— In 2022, they stepped up their protection of forests and adopted a national strategy for the protection of the Arctic.

— The United States has joined the coalition to protect the oceans and has allocated $2.6 billion to the Ocean Conservation Pledge for this purpose.

— USAID's international programs are worth several hundred million dollars a year and provide funding for international biodiversity conservation projects.

The United States has been a member of IPBES since its creation in 2012.

What is the agenda for COP 16?

One of the main objectives of COP 16 is to evaluate the implementation of the COP15 commitments and their integration into national strategies. This is particularly important now that we are only 6 years away from the 2030 deadline, and we need to avoid the fate of the Aichi targets, which were adopted too late in national policies and therefore only partially achieved. To strengthen the implementation of the GBF, COP 16 will have to adopt the modalities of the global review process, which should begin in 2025 and end at COP 17 in 2026, and continue to mobilise signatories to commit to national targets.

The points to which particular attention will be paid include the mobilisation of resources for biodiversity, the operational framework of the agreement, and the implementation of the mechanism for fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the use of genetic resources. This last point is an important issue for developing countries.

The Convention places considerable emphasis on assessing the state of biodiversity in its various components. Finally, improving research and scientific cooperation, as well as raising public awareness of biodiversity issues, are also among the major challenges of this future COP.

1. IPBES: Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES is an independent intergovernmental body with over 130 member states.

2. Financing situation for nature 2023, 9 December 2023.

3. 23 september 2024.